An issue, dominated more than usually, by typographic personalities. Steven Heller’s profile of the great American designer Paul Rand, brings to mind Rand’s comment on the ‘national’ nature of typography: ‘Good typography, American or otherwise, is not a question of nationality but of sensitivity to form and purpose.’

Yet there is a cultural heritage reflected in the typographer’s work which remains detectable even while boundaries are crossed and design goes ‘global.’

Witness the work of Brazilian-born Mary Vieira, retaining the influence of her period in Switzerland despite her absorption into Brazilian surroundings. Plus the intuitive discipline, never lost, in the craft of graphic design pioneer Hans Schleger. More evidence is presented through the essential Britishness of the late, very lamented Phill Grimshaw.

Studies in character and design, broken up by interludes. One can read the images in David Gibson’s striking photographic essay. Discover Jilly and Ian McLaren’s intriguing story of the very pre-Euro currency from Neustadt, Germany.

Contents:

- Intro

- Reviews – Editorial team

- The work of Mary Vieira – Prof. Friedrich Friedl

- Notgeld from Neustat – Jilly & Ian McLaren

- Paul Rand laboratory – Steven Heller

- Lines of movement for a graphic journey (Photography) – David Gibson

- Hans Schleger: starting from zero – Hans Dieter Reichert

- Phill Grimshaw: a character study – Mike Daines

- A-Z of Type Designers – Editorial team

The Original Text

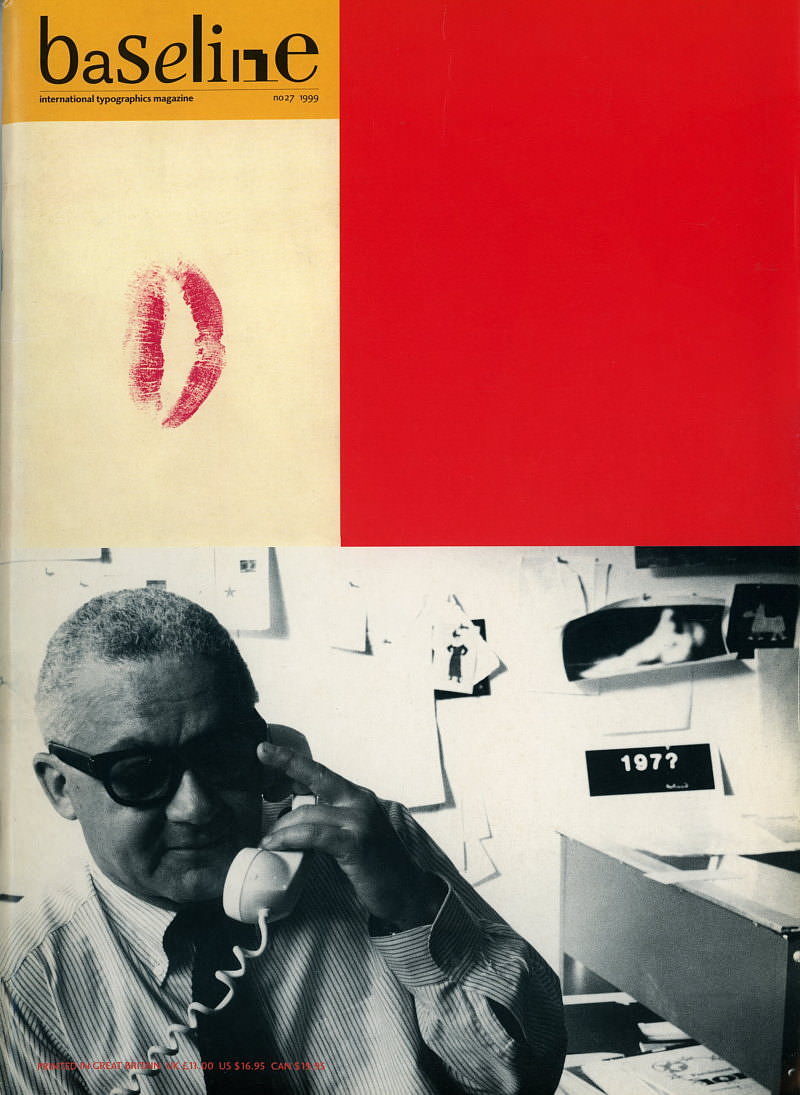

By Steven Heller

Steven Heller reviews Rand’s book covers and gives a glimpse into the creative process.

Like a painter who reaches catharsis moving paint, Paul Rand moved type, juxtaposed geometric forms, and manipulated colour masses to frame ideas. ‘Looking at Rand’s designs,’ an admirer wrote, ‘one never has a doubt whether this line should go that way, whether this shape should not be a little larger or smaller, or whether a green star might not be better than the blue circle.’ And this was never more evident than in his book jackets and covers created between 1944 and the late 1960s.

Overshadowed by his early advertising and later corporate careers, Rand’s book jackets and covers are arguably just as significant, and crucial in defining him as a pure artist with a unique vision. Amidst his overall experience book design was simply a logical expansion of his general practice. But this was a field particularly mired in mediocrity, governed by marketing conventions, and more often than not, indifferent to content. Many publishers scrutinized the interior typography of their books, but surprisingly few were concerned with how their books were wrapped. Jackets were considered necessary evils, the province of marketing departments designed as advertisements to hook customers into consuming on impulse. Book designers and editors alike referred to them as unwanted appendages of the pristine book. Nevertheless, the jacket was prime for revamping when Rand was hired to help improve a few progressive publishers’ presentations.

For Rand, book jackets were no different than any other medium that could benefit from good design. In fact, they were better. A jacket did not have to be slavishly literal but rather convey moods or interpret content. Not only were graphic symbols the perfect shorthand; colour, shapes, and lettering could evoke the requisite cues. Presumably the designer could have more control if the advertising and marketing experts could be kept at bay. And since Rand was already rather skilled at controlling this particular foe, he had no stumbling blocks. In fact, Rand always worked with sympathetic clients. Wittenborn & Company (later Wittenborn, Schultz), for instance, gave him ample licence to push the boundaries of their artbook jackets and covers. He used all the methods in his growing repertoire to give each book an individual presence, as well as an overall Wittenborn identity. Advertising had taught him the virtue of anchoring concepts to a consistent design element, such as a logo. In the case of the Wittenborn books, consistency was achieved through gothic titles typeset unobtrusively to underscore the contemporary spirit of the books. The rest depended on the content of the book.

Rand’s earliest jacket for Guillaume Apollinaire’s The Cubist Painters (1944) was his first attempt at pure, non-representational abstraction; smudges of colour adorn the jacket, with a simple, unobtrusive line of sans serif type for the title. This jacket was the prototype for The Documents of Modern Art series, and not only did it differ from typical American artbook jackets, which convention dictated were either all-type or showed a detail of a painting, Rand’s interpretation, which was consistent with his dictum against copying, did not even mimic the Cubist style. Rather it evoked the pith of the revolutionary artform. Designing artbooks in such an ‘artistic’ way might seem quite appropriate to the subject, but before Rand it was exclusive primarily to European avant garde designers. By using Italian Futurist and Bauhaus books among other touchstones, Rand developed a vocabulary of shapes and colours that evoked modernity. He also used a medley of antiquated visual elements in collages to illustrate ancient and classical art. For the jacket of The Origins of Modern Sculpture (Wittenborn, Schultz, Inc. 1946), he juxtaposed two silhouettes an ancient sculpture and Brancusi’s sculpture of an egg (a pun on ‘origins’) divided by a small line of sans serif type. Through this iconic pairing he astutely summarized centuries of artistic evolution.

In 1945 Alfred A Knopf, one of New York’s most prestigious, small literary publishers and a design conscious bookman with a penchant for fine typography and illustration, invited Rand to join an eclectic repertory of classical and modernistic designers, including W A Dwiggins, Rudolf Ruzicka, Ernest Reichl, and Warren Chappell, among others. As a condition of his initiation he was asked to do a version of Knopf’s Borzoi logo. The sleek Russian hound whose running silhouette was stamped on every spine, was rendered by other designers in pen and ink or woodcut usually in a traditional manner. Always inclined to be contrary, Rand graphically reduced the sleek canine to a few simple straight lines at right angles, with a full stop for an eye. Prefiguring his later make overs of venerable corporate logos, this was a textbook example of Rand’s ability to redefine a visual problem and devise an alternative solution that pledged allegiance to the original form. Knopf was quite taken with the audacity of the designer in transforming the mark yet retaining its essential mnemonic quality.

Like the Borzoi logo, Rand’s first jacket for Knopf, Thomas Mann’s Tables of the Law (1945), raised eyebrows at the time publication. It was certainly Knopf’s most reductive jacket. The image was a dramatically lit, mortised photograph of the head of Michelangelo’s ‘Moses’ partially covering the stacked lines of gothic type, which screamed out, ‘The Law.’ The solid brown background did not fill the entire image area but like a window shade stopped before reaching the jacket’s bottom, leaving a channel of white space that gave an illusion of three-dimensionality against the base of the image. The jacket’s ad hoc quality gives an impression that Rand cut and pasted the art and type together in an instantaneous burst of creative energy reminiscent of a Dada collage. In fact, he labored over his solution until he achieved the appearance of an accident, everything was precisely composed, yet slightly off kilter.

Manipulating ragged cuts of paper and torn photographs, often using an informal, hand-scrawled script, Rand’s jackets and covers were like playthings. Perhaps in another life he would have been a toymaker because he enjoyed combining shapes, colours, and objects into sculptural cartoons. Yet there was a serious side to this. ‘I use the term “play”, but I mean coping with the problems of form and content, weighing relationships, establishing priorities’, Rand explained years later in Graphic Wit. Each book title offered him the stimulus and rationale to play with or manipulate a multitude of forms, from drawing to collage, from lettering to type. There was never a preordained format or formula.

Scores of jackets and covers illustrate Rand’s play principle at work, but two of his favourites, created 12 years apart, exhibit how Rand’s experiments evolved. The first was a jacket for Nicolas Monsarrat’s Leave Cancelled (Knopf, 1945), a tragic tale of lovers separated by war. The second was for James T Farrell’s H.L. Mencken: Prejudices: A Selection (Vintage 1958), an analysis of the social critic’s most biting essays.

For Leave Cancelled Rand requested that ‘bullet’ holes be die-cut through the cover photograph of Eros, the god of love. The technique was unheard of with a trade book at that time indeed everything about this jacket was so unprecedented and fanciful that Alfred Knopf’s wife was reported to have called the final result an ‘expensive extravagance.’ Rand also designed the binding, which featured an embossing of a simple line drawing of the broken hands of a clock, symbolizing the protagonist’s premature return to the battlefield. Rand took his inspiration from European avant garde art books, but he also prefigured contemporary artists books in the introduction of tactile materials.

Rand was more limited in what he could do for the cover of H.L. Mencken: Prejudices: A Selection. The budgets for paperback covers were even smaller than for hard cover jackets, consequently the printing options were fewer. Yet Rand recalled that his solution was built into the raw material that he was given. Starting with a ‘lousy’ photograph of Mencken he magically produced a comic image that became a virtual logo for the writer. ‘What could one do with a bad portrait of the guy?,’ Rand explained in Graphic Wit: ‘I cut up the photo into a silhouette of someone making a speech, which bore no relation to the shape of the [original] photo. That was funny, in part because of the ironic cropping and because Mencken was such a curmudgeon.’ The result was a kind of paper doll in the form of an oratorical statue. The ragged contours of dIe cut photograph dictated that a hand-scrawled title and byline be dropped out of irregularly cut and randomly positioned colour boxes. Each of these elements was crude, but in total the pieces fit perfectly together. The Mencken cover echoed the informality of Futurist and Constructivist book covers from the 20S, but was far ahead of its time in American trade publishing of the 50S.

At Knopf, ‘Rand’s ideas were never questioned,’ recalls Harry Ford, production manager and art director from 1947 to 1959. ‘We bent over backwards to give Paul what he wanted because he was so good.’ Booksellers were ‘bowled over, simply taken aback by his work,’ continues Ford. ‘They would always give prominent display to his book jackets.’ In fact, competitive publishers were also impressed with Rand’s talent, but Ford presumes that ‘since most publishers were set in their ways, few wanted to copy what Rand did, Nevertheless, there was widespread agreement that his method was revolutionary.’

Although the Knopf (and then, later Vintage, Doubleday, Atheneum, Harvard, and Harvest Books) jackets and covers were ostensibly illustrative in a modern sense, Rand continued his exploration of pure abstraction with jackets produced between 1956 and 1964 for the Bollingen series, published by Pantheon Books. Using colour fields, geometric and amorphic shapes, and random splatters combined with his distinctive scrawl, these jackets were more akin to small canvases than conventional wrappers. And while they were overtly less playful than his other, mass-market jackets, they were no less eye-catching and in a way even more timeless.

The Bollingen Foundation was founded in 1947 by the Andrew W Mellon family to publish works by psychoanalyst Carl Jung. In addition to Jung’s own books and essays, and those by Jungian scholars, Bollingen also supported art and ‘social histories, notably E H Gombrich’s Art and Illusion, and published papers presented at the prestigious A W Mellon lectures. Rand’s jackets were never killed and in return, he developed an unmistakable identity that underscored the serious aim of Bollingen while telescoping the accessibility or ‘friendliness’ of the list. Rand did the Bollingen jackets until 1964.

Among the designers in the modern camp with whom Rand had an affinity, and perhaps a healthy rivalry, Alvin Lustig, an American-born designer of books, magazines, textiles and sign systems, was the most prolific. Lustig (along with former Bauhausler Herbert Bayer) was also invited by Alfred Knopf to design jackets. But Lustig had made his name starting in 1940 as a designer for the small literary publisher, New Directions (which shared the same floor as Pantheon Books). At that time he was making imagery from hotmetal typecase ‘furniture,’ a similar method to that for Russian Constructivist books by Lasar, El Lissitzky and Alexander Rodchenko. By the mid 40s, however, when he was designing all the jackets in New Directions’ New Classics series, Lustig had combined modern type with abstract line drawings, or what he called symbolic ‘marks,’ which owed more to the work of artists like Paul Klee, loan Miro, and Mark Rothko than to accepted commercial styles. Like jazz improvisations, these non-representational images signaled the progressive nature of his publishing house. During the late 40s he introduced collage/montage and reticulated photography, evoking surrealistic fantasies. And in the early 50s he developed a series of paperback covers for Noonday and Meridian Books using only gothic and slab serif typography. Rand and Lustig clearly shared certain traits since they were both fluent in the language of modernism each had a similar preference for contemporary typefaces and child-like scribbles but each interpreted modernism in their own ways, and no doubt competed for who could alter the form faster. Some insist it was a dead heat.

Steven Heller is currently preparing a biography about Paul Rand to be published by Phaidon Press.