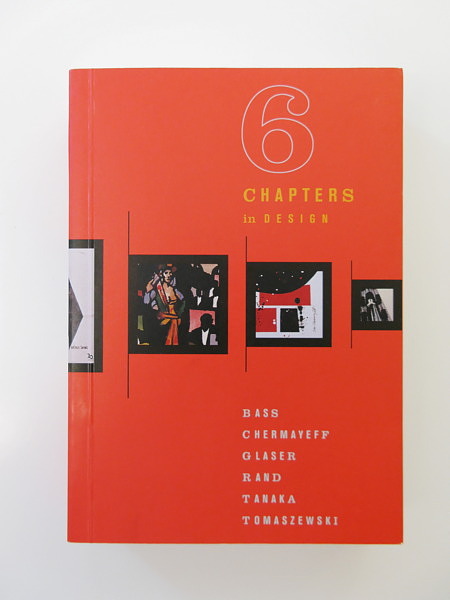

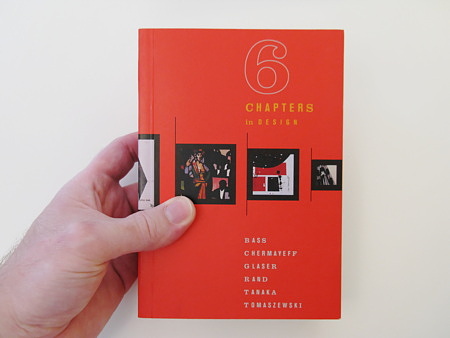

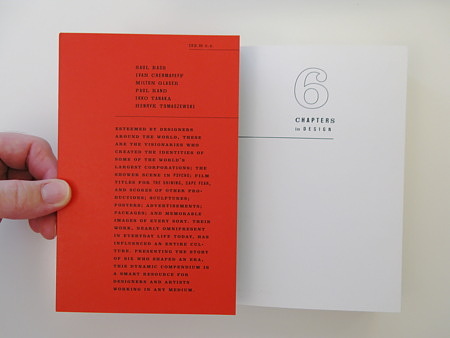

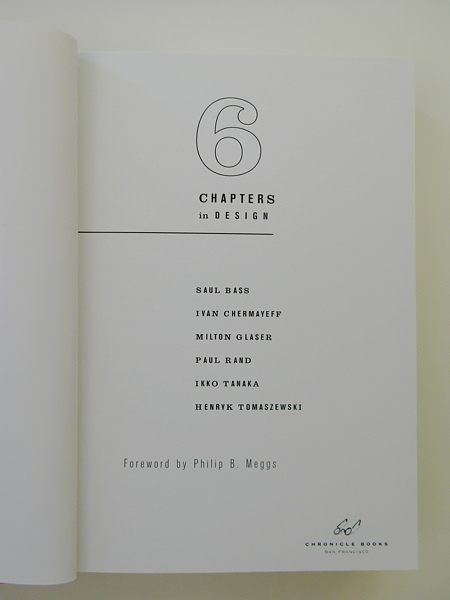

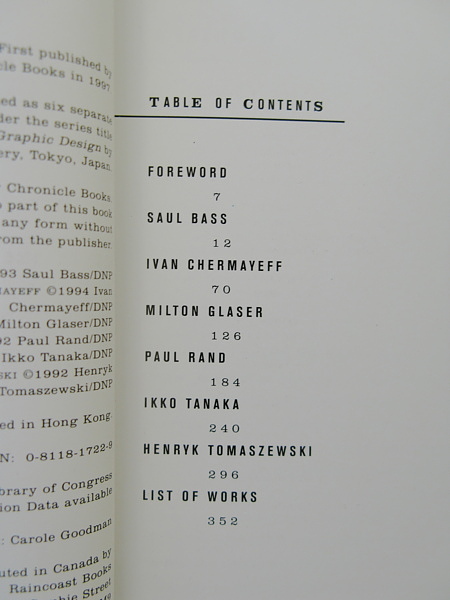

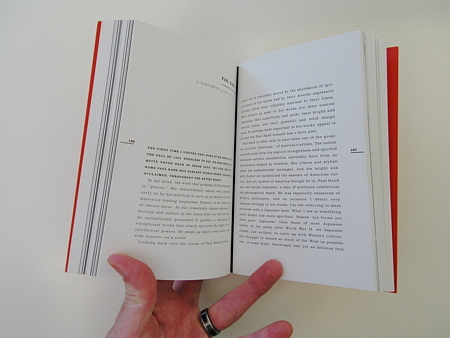

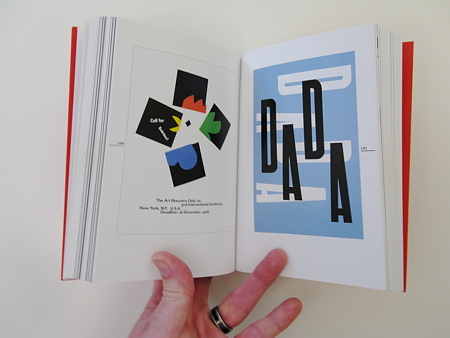

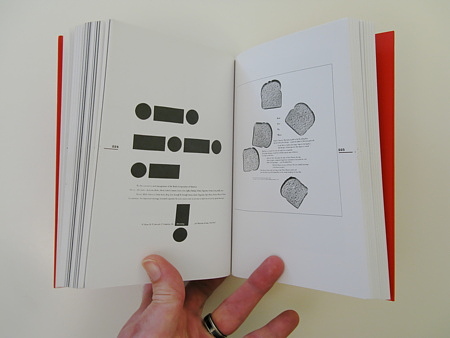

Stylish and concise, this volume presents the work of six venerable names in modern design history. Featuring more than three hundred examples of their best work, yet still eminently portable, Six Chapters in Design is a charming model of economy.

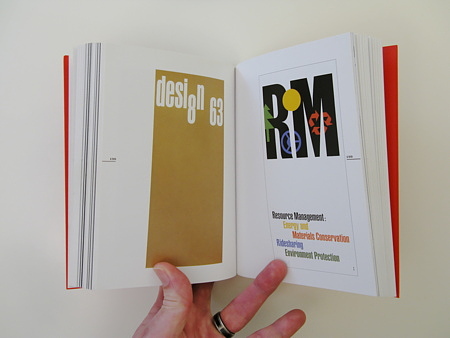

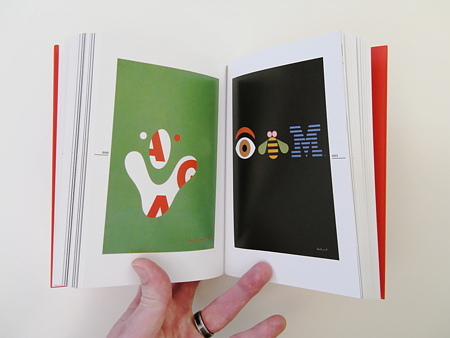

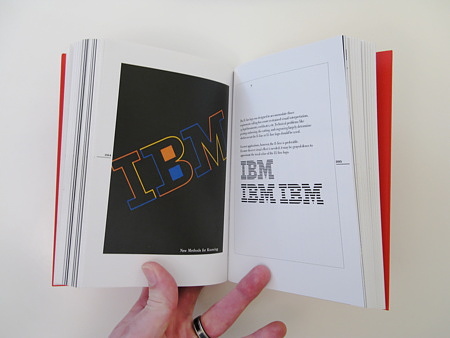

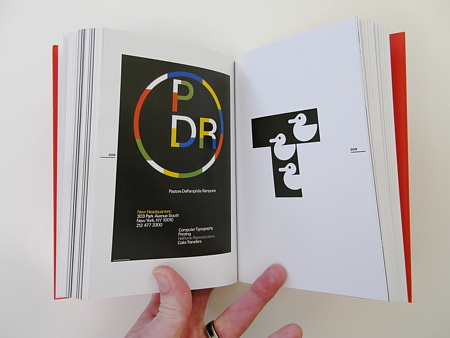

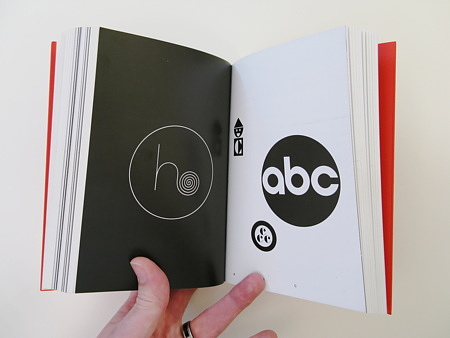

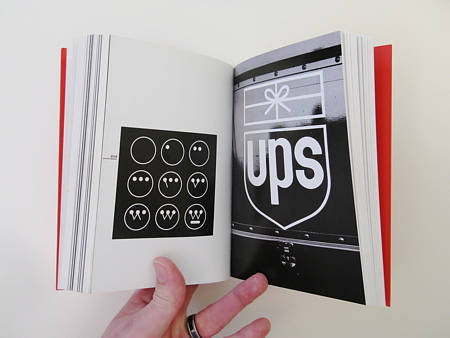

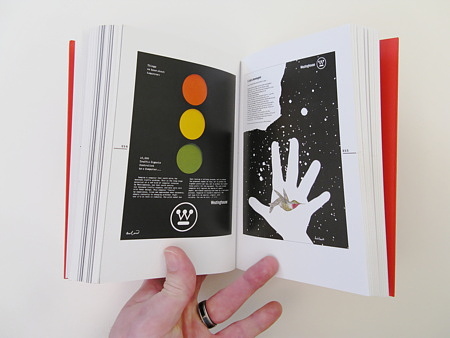

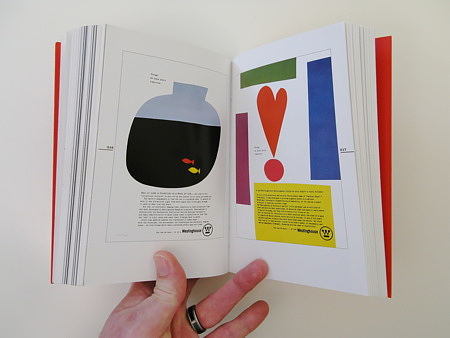

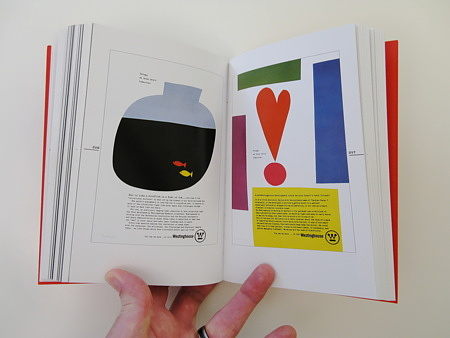

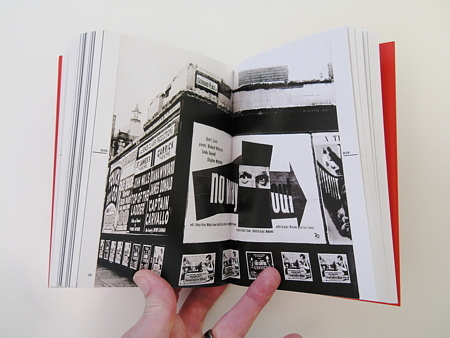

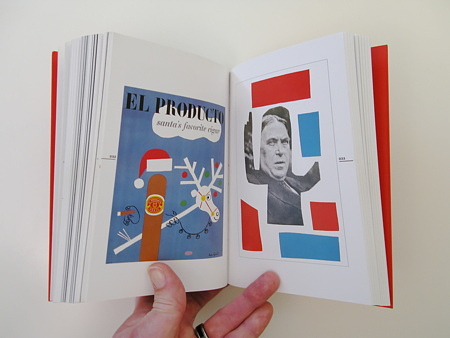

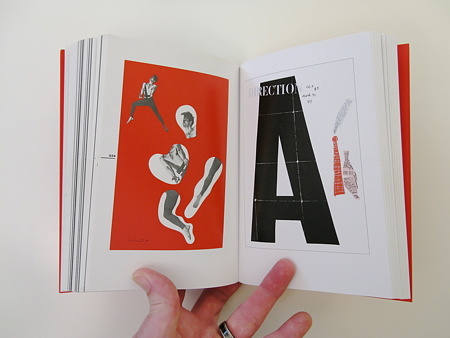

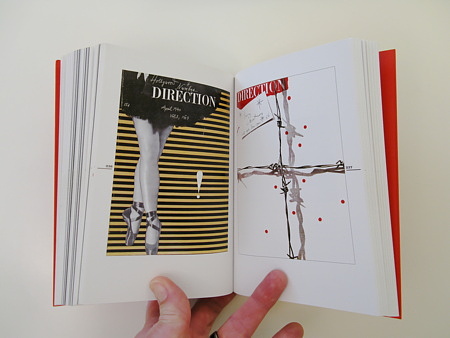

Each chapter begins with an essay by a fellow designer, or poet, or, in the case of Saul Bass, director Martin Scorsese, and closes with a biographical profile. Esteemed by designers around the world, these are the artists who created the identities of Warner, AT&T, IBM, ABC, UPS, and Westinghouse; film titles for The Shining and Cape Fear; posters; advertisements; and memorable images of every sort.

Their work, nearly omnipresent in everyday life, has influenced an entire culture. This dynamic compendium is a smart resource for designers and artists working in any medium.

The Original Text

By Yusaku Kamekura

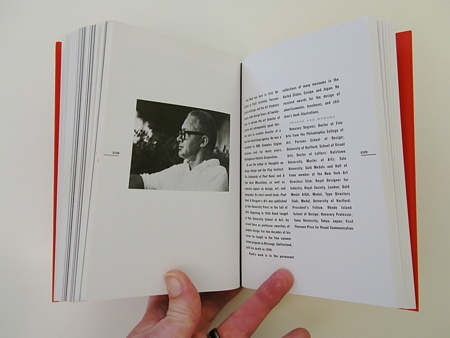

The first time I visited Paul Rand at his home was in the Fall of 1954. Needless to say, we were both still quite young back in those days. Yet even then the name Paul Rand was already widely know, and widely acclaimed, throughout the entire world.

In my mind, the word that probably fit Paul Rand best is “genius.” His extraordinary talents were confirmed early on by his selection to serve as art director of one of America’s leading magazines, Esquire, at the tender age of twenty-three. As his remarkable talents continued to develop and mature in the years after our first meeting, he energetically proceeded to produce a succession of exceptional works that clearly mirrored the depth of his intellectual powers. He swept up nearly every price — and wide renown — as a result.

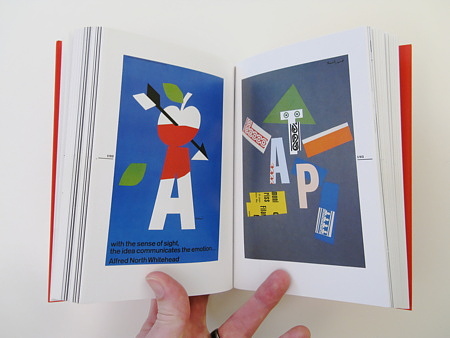

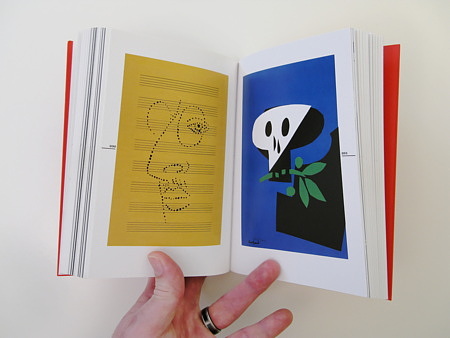

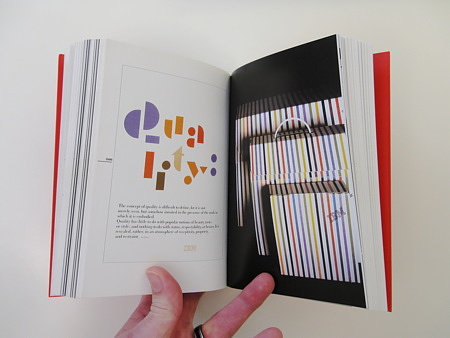

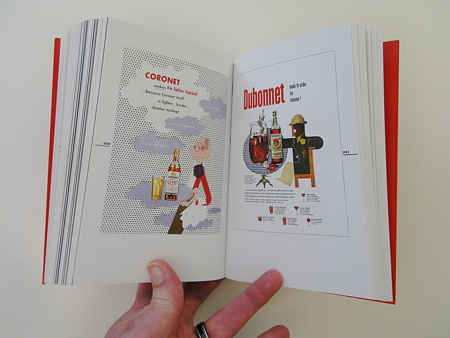

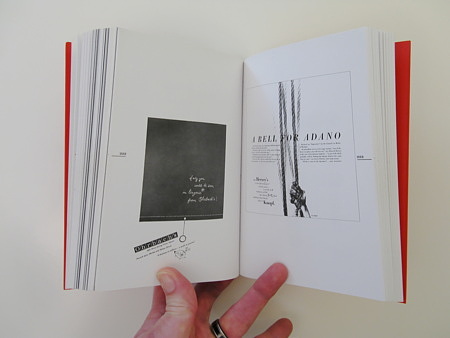

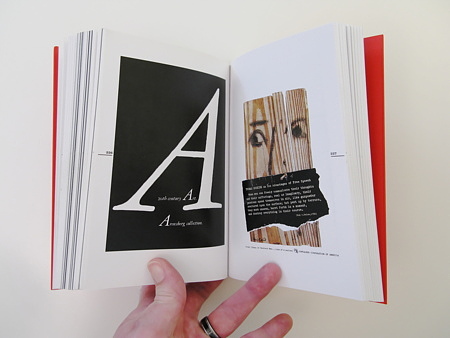

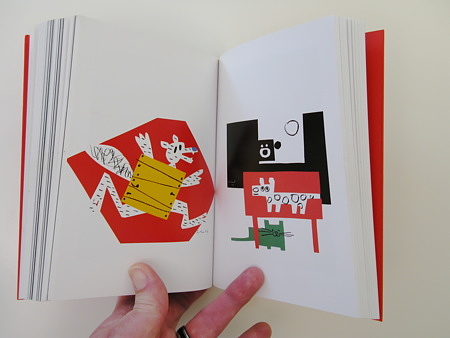

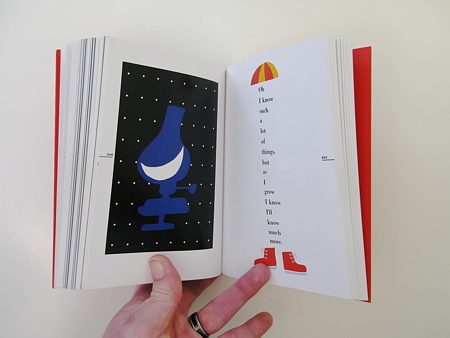

Looking back over the course of Paul Rand’s artistic career, one is inevitably moved by the abundance of lyrical beauty in his works and by their diverse expressive methods, which were infallibly matched to their times. What attracts us most in his works are their concise expression, their superfluity cast aside, their bright and cheerful colors, and their powerful and solid design sense. Yet perhaps most important to his works’ appeal is the fact that Paul Rand himself was a born poet.

Paul Rand is often said to have been one of the greatest, and most “American,” of America’s artists. The notion no doubt arose from his explicit straightness and spirited brilliance — artistic sensibilities inevitably born from an environment shaped by freedom. His urbane and stylish ideas, his sophisticated messages, and his bright and witty humor all symbolized the essence of American culture. And yet, symbol of America though he is, Paul Rand was, one should remember, a man of profound intellectual and philosophical depth. He was especially enamored of Eastern philosophy, and on occasion I detect very Japanese feelings in his works. I’m not referring to mere exoticism with a Japanese bent. What I see is something much deeper and more spiritual. Indeed, his forms are often more “Japanese” than those of most Japanese artists. In the years after World War II, we Japanese rush, and writhed, to catch up with Western culture. Our struggle to absorb as much of the West as possible was, in some ways, touchingly sad; yet we believed that this was our only means of surviving. In our haste, we all too often considered Japanese traditions as a hindrance. Today, thinking back on the pressures we felt in those times, the situation seems rather heartrending.

When we Japanese look at Paul Rand’s work and ponder the futility of our struggle to absorb Western culture, we are stunned to recognize traditional Japanese styles — styles which we Japanese have long forgotten — running beautifully and refreshingly through the. Even more importantly, in his ever work we marvel at the wondrous vitality we find there that transcends all notions of time.