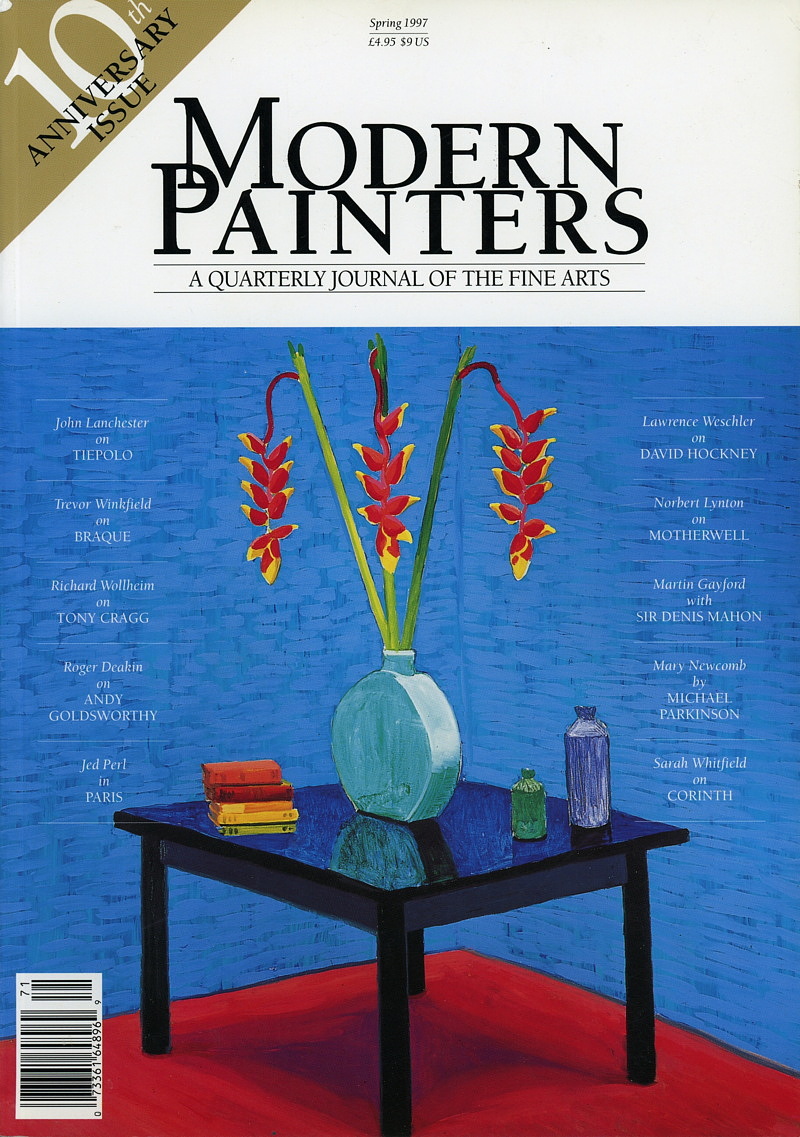

Modern Painters is a monthly art magazine published in New York City by Louise Blouin Media. The magazine is published 12 times per year; it includes profiles on two international artists per issue; columns by international contributors; interviews with and articles by contemporary artists and curators; and information on exhibitions, books, performances, biennales and festivals.

Contents:

- John Lanchester on Tiepolo

- Trevor Winkfield on Braque

- Richard Wollheim on Tony Cragg

- Roger Deakin on Andy Goldsworthy

- Jed Perl in Paris

- Lawrence Weschler on David Hockney

- Norbert Lynton on Motherwell

- Martin Gayford with Sir Denis Mahon

- Mary Newcomb by Michael Parkinson

- Sarah Whitfield on Corinth

The Original Text

By Lance Esplund

Lance Esplund celebrates the genius of Paul Rand, father of twentieth-century American graphic design.

Paul Rand died of cancer on 26 November 1996, at the age of 82. One of the first American designers to fully embrace European Modernism (and certainly its strongest American proponent), Rand, in the late 1930s and early 1940s (alongside a small group of European emigrants and transplanted Bauhaus artists), mainstreamed post-Cubist form into American ephemera, challenging the illustrative, the sentimental and the Art Deco look of American graphics with metaphorically rich, abstract forms.

Born in Brooklyn, Rand studied at Pratt Institute, Parson’s School of Design and with George Grosz at the Art Student’s League, but claimed his teachers didn’t talk of the Bauhaus:

How could one know about Jan Tschichold in Pratt Institute, or in Brooklyn, or in Brownsville, or in East New York? One knew about pool sharks and ice pick murders but not about Tschichold or the new typography.

Albeit well schooled, Rand maintained that he was actually self-taught—by studying European magazines featuring Cubist, Constructivist, de Stijl and Bauhaus artists, through a trip he made to Europe in the late 1920s (where he encountered Modernist works at first hand), and by reading the Hungarian Constructivist and former Bauhaus teacher Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s first American book, THE NEW VISION, published in 1932.

As a modest 23-year-old, Rand was already widely influential as a designer for APPAREL ARTS and art director of ESQUIRE magazine, a position he held until 1940. From there, he joined William Weintraub in an advertising agency, where he was art director until 1954 (often doing ten projects a day), designing marvellous and memorable campaigns for Disney Hats and El Producto Cigars, as well as numerous and varied DIRECTION covers (some of which he designed in trade, for Soutine, Leger and Le Corbusier drawings). From 1954 on he worked independently, designing and teaching into the last weeks of his life.

In 1946, Rand published his first book, THOUGHTS ON DESIGN (with an introduction by E McKnight Kauffer), which had tremendous influence on a whole generation of designers, and in which Rand, through nine reflectional essays, including ‘The Beautiful and the Useful’, ‘Versatility of the Symbol’ and ‘The Role of Humour’, speaks earnestly and eloquently about what makes good design. A short list in Rand’s oeuvre includes logos and corporate identity systems for IBM, UPS, ABC Television (for all three of which he showed the client only one logo design); Westinghouse, NeXT Computer, Cummins Engines, Colorforms and The Limited; hundreds of book, magazine and catalogue covers, as well as children’s books, perfume bottles, posters, packages, editorial layouts and magazine ads—whose copy he rewrote on occasion to coalesce with his designs. It is very probable that his ad campaign for Dubonnet single-handedly increased the company’s sales tenfold in the early 1940s.

Paul Rand—like Paul Klee (whom Rand greatly admired) was a master teacher. Both Rand and Klee taught extensively (Klee at the Bauhaus and Rand as a professor emeritus at Yale). Both also wrote profusely, their writing emerging out of teaching as well as the need for personal elucidation. Rand, in a 1993 I.D. magazine interview claimed: ‘I don’t write for your benefit. I’m writing for myself, to understand. The by-product is a book for other people’. Klee’s massive, posthumously published, two-volume Bauhaus teaching notebooks—THE THINKING EYE and THE NATURE OF NATURE, which clearly and exhaustively expound on the creative process and the making of art (as well as the nature of the Universe)—have been compared in their meaning and importance to modern art with Leonardo’s writings in the Renaissance. Rand listed Klee’s writings in the bibliographies of his own books, and made references to Klee (as well as Cezanne, Miro, Braque, Kandinsky, Mondrian, Man Ray and Arp, among many, many others) in his own writings, interviews and lectures. When asked, less than two months before his death, to autograph one of his designs—a 1948 Klee Foundation exhibition catalogue, Rand suggested that his cover design was so close to Klee’s own work, that Klee, not he, should inscribe it.

Rand’s own books, THOUGHTS ON DESIGN (1946), A DESIGNER’S ART (1985), DESIGN FORM AND CHAOS (1993) and FROM LASCAUX TO BROOKLYN (1996), are extremely erudite on art, aesthetics and the making of graphic design which, Rand claimed, he approached no differently from making paintings. The books are all beautifully designed by Rand, illustrated with his own work and (as he contended that art does not have to do with genre, but with quality) juxtaposed with a variegated potpourri, including masks, cave paintings, Chinese pottery and Egyptian hieroglyphics, fisherman’s buoys, eye-charts and a Shaker flatbroom, the Florence Baptistery, the Katsura Palace and the Leaning Tower of Pisa. To illustrate a point about the integration of form and content, Rand includes ‘Tipu’s Tiger’—an eighteenth-century, metre-long, wind-up tiger, atop a prone man, and dining on his neck—which Rand described:

This wooden effigy, a kind of non-musical hurdy-gurdy that simulates the growls of a tiger and the cries of his victim, is at first disturbing. But its expression and scale are so toylike, its colour so brilliant, that the impression is merely startling. A tragic event treated in a lighthearted manner combines to create the humorous effect… The delicate handling of the decoration and the fanciful form of the tiger make a dramatic foil to the deadly nature of the occasion depicted.

It is not, however, only through Klee’s and Rand’s teachings and books that their often so-similar lessons can be gleaned; it is in the works themselves. In a catalogue interview that accompanied the 1989 Walker Art Center’s show ‘Modern Painters: A Visual Language History,’ Rand said:

When I was doing a cover for DIRECTION, I was really trying to emulate the painters. I was trying to do the kind of work Van Doesburg, Leger and Picasso were doing—to work in their spirit… Even in advertising design my models were always painting and architecture: Picasso, Klee, Le Corbusier and Leger.

Artists and designers (two words Rand used interchangeably) have always used contemporary and past artists as sources, seeing the connections within the traditions of form-making that are relevant to their own work. The art historian Meyer Shapiro took Fernand Leger to the Pierpont Morgan Library specifically to view the tenth-century Spanish illuminated manuscript the Morgan Beatus; Rand compared the compact clustering of figures and objects in a Leger ink drawing (from his own collection) to the coalescence of horse, rider, ornament and flora on a Romanesque capital; Matisse spoke of Delacroix and Ingres as being links in the same chain; Cezanne ‘redid Poussin after nature’; Picasso stated (and Rand partially quotes this in FROM LASCAUX TO BROOKLYN):

To me there is no past or future in art. If a work of art cannot live always in the present it must not be considered at all. The art of the Greeks, of the Egyptians, of the great painters who lived in other times, is not an art of the past; perhaps it is more alive today than it ever was.

Rand clearly understood his connection to the past and the present, and, although he used modern artists as mentors, he also spoke of his formal connections (through them) to Masaccio, Cimabue, Rembrandt and Breughel, cave art and the Brooklyn Bridge—FROM LASCAUX TO BROOKLYN.

In the introduction to a monograph of Josef Muller- Brockmann, Rand, praising the Swiss designer, wrote:

His posters are comfortable in the worlds of art and music. They do not try to imitate musical notation, but they evoke the very sounds of music by visual equivalents—not a simple task.

Not a simple task indeed, but one that Rand (and Klee) believed is essential—and achieved consistently. Like Robert and Sonia Delaunay and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Rand moved into the realm of pure, poetic colour-relations, having understood the rhythmic, metaphoric, emotional equivalents between colour and music— seeing that colours are to painting what words are to poetry. ‘To design’, Rand wrote, in DESIGN FORM AND CHAOS, ‘is to transform prose into poetry’. Rand understood and utilised metaphoric forms, the building blocks of poetry, as opposed to the hard- sell, illustrative and narrative forms used by other designers, who, Rand claimed in THOUGHTS ON DESIGN,

by interpreting and rendering an abstract idea literally or naturalistically, often denied the advertisement the potentialities of the abstract symbol, its power to suggest and conjure up more than would be possible by other means…it is in a world of symbols that the average man lives. The symbol thus becomes a common language between artist and spectator.

Paul Klee, in his CREATIVE CREDO, wrote: ‘Art does not reproduce the visible but makes visible’, and in THE THINKING EYE:

There are some who will not acknowledge the truth of my mirror. They should bear in mind that I am not here to reflect the surface (a photographic plate can do that), but must look within. I reflect the innermost heart. I write the words on the forehead and round the corners of the mouth. My human faces are truer than real ones. If I were to paint a really truthful self-portrait, you would see an odd shell. Inside it, as everyone should be made to understand, would be myself, like the kernel in a nut. Such a work might also be called an allegory of crust formation.

Rand saw in Paul Klee (with his thousands of specific, metaphoric structures) and in Jean Arp what must have been for him, at the beginning of his career, the equivalent of what Giotto was for the artists of the fourteenth century. In Paul Klee’s “Rough-Cut Head,” a sculpturally full ink wash from 1935, a cubist faceting reveals an unfinished or ‘rough-cut’ child’s head, with a tree trunk-like neck, broadly hewn from a cold but light reflecting stone. Diamond? Crystal? The ground plane angles forward, to butt up against the head, as if head and dark ground were of the same substance. Milky washed planes flatten and warp across the surface with enormous elasticity, relocating themselves constantly, but never losing their solidity or their liquid depth. Tiny slits mark locations for eyes and a mouth, as if they were stitches unifying the intersections of plane-to- plane. A child, fresh, merged with its surroundings, innocent, wide open, afraid, coming into being, pliable yet hard as rock, soft, sharp, striving, unfinished and alone—the associations go on.

Rand found a similar impetus in Arp, in collages, sculptures and drawings that seem to encompass the whole world within a single piece. The titles alone, as in Klee’s works, stop just short of poems. Marble sculptures like “Awakening,” “Growth,” “Dream Flower with Lips,” “Torso-Sheaf,” “Torso-Fruit” and “Shepherd of the Clouds,” in which you experience human forms merging with plant, animal and fruit forms: lips, elbows and open mouths; tree limbs, horns, bones, shoulders, chins, hips, buttock and breast; ballerinas on point, birds taking flight and an infant emerging from the womb; fingers, heads, wings, leaf, liquid and air; the inner structure, its microscopic world and its seemingly transparent surface, all flood you as you move around these impossibly weightless bodies.

Rand, the visual punster, produces seemingly dashed-off, circular forms that on the same book cover are forever open in analogy, and (depending on their context) read as a cigar butt, a nose, buttons, a flower, single pupils or whole eyes, portholes on a ship, the opening of a smoke stack, spots on a cat and the pimiento in an olive. Even in a logo, like the one Rand created for United Parcel Service (UPS)*, a wide range of analogies appear: a present, a shield, a medal, a family crest, military insignia, a flag, a coat of arms, a mask, a cattle brand, or the days of yore—with canvas mail trunks. Or take the Westinghouse logo, which resembles a face or mask, a light bulb, a plug or receptacle, a human being, a printed circuit and (of course) a W.

Among the many books and book covers Rand designed were a number for Alfred A Knopf, including the Thomas Mann novels, THE TRANSPOSED HEADS, A LEGEND OF INDIA (1941) and TABLES OF THE LAW (1945). THE TRANSPOSED HEADS is a classic East Indian tale that Lionel Trilling described as ‘at once the quintessence and the reductio ad absurdum of all love triangles’—a story in which two best friends literally lose their heads, only to have them transposed by the story’s heroine as the bodies are resurrected. Rand’s cover is as rich as Mann’s fable, and reveals its ever- increasing depth, the further into the story you read. Rand merges three heads, three necks, three sets of shoulders and chests, with three sets of hips, waists and bellies, all into one black, hourglass, figurative form that moves like a Jesse tree. This is placed over a ground made up of an acidic-yellow and orange Indian cloth, with a pattern of tiny headless bodies, and a shocking-pink rectangle; both are separated by a slicing, horizontal white stripe. Pregnancy, the interchangeability and compatibility of forms, the flowing and intermixing of energies and bodily fluids, generational growth and decapitation—all are experienced in this poignant, though oddly anonymous, multi- onion-domed, sexy, Arp-like form. The handwritten script lightens the mood of this sanguinary tale, but the crosses on the ‘T’s and the ‘H’ still cut through the letters, like the brandishings of the novel’s decapitating sword.

In 1950, Rand designed a 24-sheet poster for Mankiewicz’s film “No Way Out” that has the clarity of a Russian Constructivist painting. A long, flat, horizontal red arrow moves from left to right across a white ground, and is broken in two by a large, black vertical form; on top of this is slapped a smaller, horizontal, prison-door-like slotted opening, out of which a face with two closely framed eyes pops forward and stares suspiciously. The arrow ascends before the break, only to drop like a guillotined head afterward. ‘No way out’ is written in large, white lower-case type across the arrow, ‘out’ having been separated by the break. A long, black triangular form slices downward through the top of the white letters, unifying the arrow into a painfully steady descent. Every sharp geometric form butts its head against another, appearing to shift or jerk them both in the collision, not only sideways, but also forward and back— opening up the space, like some kind of vivisection. This huge poster (when seen in full scale) has the presence and speed of a King-Kong, one-two knock-out punch, or a fire engine whizzing past. In a photograph of it from 1950, on the side of a building, it renders lifeless a number of smaller posters for other films surrounding it, one of a badly drawn couple, romantically embraced, and many large, monotone, type-ridden posters, filled from top to bottom and side to side.

Rand’s work, always appropriate and constantly varied, is the perfect marriage between those things American—the ever- changing newness, the brashness, the childlike innocence, the running-ahead-and-catch-me-if-you-can attitudes, the commercialism and the ticker-tape parades—and the European traditions that fostered Matisse, Dufy and Picasso. Rand allows us to re-experience, through the everyday objectness of familiar images and ephemera, the richness of visual relationships, through puns, games, unsolved puzzles and riddles. In a Rand design the unexpected surprisingly springs forth like a rabbit from a magician’s hat; the seemingly simplistic becomes the wittingly sophisticated—charming, elegant and humorous. Calderesque shapes skip through his designs, trailing incisive Klee-ish lines that at once become a child’s scrawl, a kite tail, an ocean wave or the contour of a dove. His work, like Miro’s and Chagall’s, belongs to the realm of play and fantasy that invokes the same satisfaction I find in watching animals come to life through the metamorphosis of clouds. To walk through an exhibition of Rand’s work, or even to leaf through one of his books, is to return to childhood: to play with whirligigs, teeter-totters and swings, to play hop-scotch or to visit the circus (to which Rand often referred) with its wonderful range of scale and texture—elephants and men on stilts appearing out of striped walls in big tents; tiny tight-rope walkers balanced oh- so-very-high-above on thin wires; roving spotlights illuminating somersaulting monkeys, human cannonballs, brass bands, acrobats and clowns—or to watch amusement park rides with their chase lights and their gravity-defying, twisting, linear movements. Is it any wonder that Rand loved Leger (a man who would comically throw himself down a flight of stairs after dinner to entertain his guests) with his paintings of cyclists, machine-like forms, circus performers, jumbled figures and construction workers, all mixed together with those broad, bright brushstrokes of red, yellow and blue? Or Breughel, whose work Rand describes in FROM LASCAUX TO BROOKLYN:

The texture of Breughel’s pictures is a complexity of contrasts, movements and expressions united in a symphony of light and shade, curves, angles and emotions—the whole gamut of conflicting phenomena. In Breughel’s ’Children’s Games,’ sturdy buildings serve as visual backdrops for frolicking kids; the passive and the active, simplicity and complexity, are in harmony. Each compact and stocky little figure seems to have been patiently whittled out of some magic substance. And each game, though clearly articulated, seems somehow to be part of one giant ensemble of fun and frolic. In the end one experiences the collective joy of children, colours and forms at play.

Rand and Modernism have been mentioned together so often that their union has become almost banal. During Rand’s public appearance, held in conjunction with Cooper Union’s 1996 retrospective of his work, someone blurted out, ’What do you think about Modernism?’ (as if, let’s humour him, and, this ought to get a rise out of the old guy). Rand was a man who, when asked, ‘how did you design the Yale colophon?’, held up his hands for view, and replied simply and humbly, ‘Compass. Ruler’. There was an overriding tone in that lecture hall that recalled curious onlookers at a museum specialising in the American pioneer: respectful of this trail-blazer though they were, people still seemed unconvinced that Rand, this ‘past’ icon of graphic design—a man who was still writing essays titled ‘Form and Content’, a man who still spoke highly of Klee and Mondrian, who now was in Cooper Union’s Great Hall and had recently written, ‘Both in education and in business graphic design it is often a case of the blind leading the blind’—could be of any real use to them. And this, moreover, was a man who, in a 1996 essay titled ‘From Cassandre to Chaos’ wrote:

H L Mencken’s caustic, but hilarious critique of Warren G Harding’s inaugural address roughly echoes my feelings about the state of much of design today: ‘It reminds me of a string of wet sponges; it reminds me of tattered washing on the line; it reminds me of stale bean soup, of college yells, of dogs barking idiotically through endless nights. It is so bad that a sort of grandeur creeps into it. It drags itself out of the dark abysm of pish and crawls insanely up the topmost pinnacle of posh. It is rumble and bumble. It is flap and doodle. It is balder and dash’.

In a photograph of Rand’s studio, taken in the 1950s, tacked to the wall among a number of childlike drawn animals, toys, collages, paintbrushes, paints and a mask are: a drawing of a lightbulb shape with two pencil-point eyes that resembles a frightened child; a dog whose spots (that seem to have only moments ago freed themselves from his body) fill the space of the page, and are snowing everywhere, one landing and becoming his nose, another his eye; and a line drawing of a cat, with its tail looped around its body like a scarf around a human neck. A black form resembling a book, open, facing inward and exposing its spine to our view, covers the cat like a mask, as two white eyes bullet through the darkness, creating a multi-reading of a human face, a Batman-type, masquerading figure and a cat. In this clearly unstaged photograph of an artist’s working process, I see the child-man who produced the children’s book SPARKLE AND SPIN: A BOOK ABOUT WORDS (1957), in which the homophones pair/pear and hair/hare are illustrated through the repetition of the same shape, used as a pear on one page and a pair of pear-shaped hares on the facing page, or who, in the ad campaign for El Producto, could envision cigars as an endless variety of human beings, or who could see letters as figures holding hands, as in the unification of the ‘imi’ in the logo for The Limited, or letters as rising suns (as in Asian calligraphy), as he did in the logo for Morningstar. I am also reminded of his Klee-like painting, “Treebird” (1954), in which the tail feathers of the bird and the branches of the tree rhythmically intermix and become indistinguishable, or of his many DIRECTION covers, one from 1942, in which he used a star for the head of a newborn chick, and one from 1940, with barbed-wire ribbon and a greeting written on a card resembling a corpse’s toe tag, all on a Christmas present-like cover, and how, in another cover from 1941, he turned the two fragments of a broken heart (already serving literally as pieces to a puzzle in an incredibly rich metaphor of war-torn lovers) into a silhouetted kissing couple. And I am left assured that like all great artists, he still has much to offer— even in his absence—for this is not a man whose time as teacher and mentor has passed.

*Rand claimed later the logo was just not right: he wanted to make the loops of the bow and the bowl of the ‘P’ circular, and to get rid of the point at the logo’s base, but when he offered to change it, the company, he claimed, ‘did not understand the metaphors’, and turned him down.

Lance Esplund, a painter who lives in New York City, is a faculty member at Parsons School of Design.