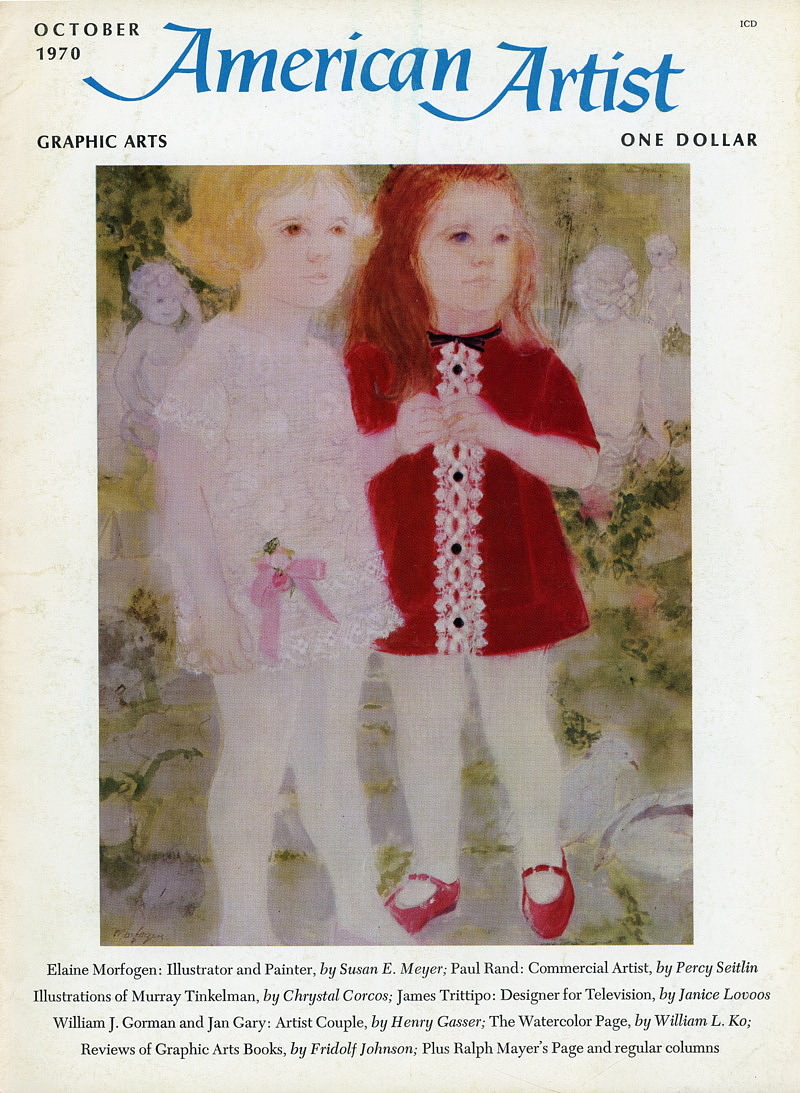

American Artist from October of 1970. Featured artist with cover illustration is Elaine Morfogen. Other articles or subjects of articles include Murray Tinkelman, Illustrator by Chrystal Corcos, James Trittipo, Television Designer by Janice Lovoos, An Artist Couple: William Gorman, Jan Gary by Henry Gasser, Watercolor by William Ko, Paul Rand, Commercial Artist by Percy Seitlin, and Elaine Morfogen, Illustrator and Painter by Susan E. Meyer.

The Original Text

By Percy Seitlin

PAUL RAND’S CAREER as a designer of ads, magazines, packages and containers, brochures, labels, trade marks, posers, books and book jackets has now spanned more than thirty-five years. After graduation from Haaren High School in his native Brooklyn, he attended Pratt Institute, Parsons School of Design, and the Art Students League. His ambition while still in high school was to become an illustrator, and although he never quite achieved the rank of the title-holders in those days, Rockwell and Leyendecker, he did do a rigorous stint as a professional illustrator with Metro Associated Services, a firm that sold stock drawings and cuts from a catalogue that covered everything from farm animals, vehicles, houses, snow scenes, children at play, and men at work, to animated headlines for going-out-of-business for fire-sale ads.

At twenty-three, Rand was art director for the firm that published Esquire, Apparel Arts, and Coronet magazines, and has been at the top of his profession since then. Although all this apparently has been a heavy continuing responsibility, Rand comments about his professional life: “When you’re young, you’re not aware of the excessive weight of responsibility—at least I wasn’t. You do one job at a time and you do your best. If, in this way, you keep outdoing yourself, you’re not too aware of it. You approach each job with the same lack of confidence. Lack of confidence can be a creative force as well as a destructive one, you know.

“I certainly am a worrier. And a good thing, too. I worried when I was young and I still worry. But as a worrier, I’ve been lucky because it has made me work hard ever since I was a kid, and I’m glad of that, glad to have spent my time worrying and working instead of playing games.”

No one asks Rand to approach and carry though every job in a creative sweat, instead of just coasting along with an excellent technique. But to do otherwise would not be Rand; he feels his obligation that same way that a fine-artist does.

His work in format design for Esquire, Coronet, and especially for Apparel Arts established his reputation as a master of graphic techniques and a designers whose art was innovative, beautiful, and invariably did more than justice to the client’s message. His work as a commercial artist is often discussed by critics in terms used in the discussion of fine art. Rand makes the distinction between “commercial” and and “fine” art very clear: “Commercial art is to fine art what applied research is to pure research in science. But each is open-ended in it own way; each offers it own world of possibilities.

“To see the commercial artist as nothing but a pitchman is a little too glib; the ‘nothing but’ part of it is that part that could be wrong. What about the special skills of the commercial artist, his way with type and typography, his knowledge of reproduction processes, his design ability, his showmanship…and, yes, his salesmanship? Besides, there are plenty of so-called fine artists who are pitchmen, too, and I wish those who, for example, use Ben-Day blow-ups (the big dots) would at least acknowledge that they learned about such techniques from commercial artists. I used Ben Day blow-ups first in 1941, and there were probably other commercial artists who were using them then, too.”

Rand has also served as art director of William H. Weintraub Advertising Agency, working on accounts such as El Producto cigars, Schenley liquors, Disney hats, and Stafford fabrics. In addition, during his long, many-sided career as a free lance artist, Rand has done advertisements, packages, displays, and promotion literature for firms such as IBM, Westinghouse, and Ford, and children’s book illustration, book design, and jacket design for many publishers, including Knopf and Harcourt, Brace and World. The quality of his art work, along with his activities on the faculty of the Yale School of Art and Architecture from 1956 to 1969, have influenced a whole generation of artists and designers for industry.

Through it all the Paul Rand style emerges:

“Of course I have a style, and I use it willy-nilly in my work as a commercial artist. Anyone who knows me could recognize my size, shape, gait, gestures and stance in the dark. My preference in forms, colors, moods, type faces, textural surfaces and line are all components of my style. It’s also characteristic of my style—as an advertising artist—to address myself to the problem of finding the design idea that will carry each job, dramatize it in graphics…But the mystery of style in design, art—advertising art, too—had better remain a mystery, lest style go out the window.”

Today, Paul Rand’s work is just as fresh, innovative, and conscientious as it was in the early forties when men like Moholy-Nagy and McKnight Kauffer began to write enthusiastically about it. Moholy-Nagy size up Rand shrewdly: “He is an idealist and a realist using the language of the poet and the business man. He thinks in terms of need and function. He is able to analyze his problems, but his fantasy is boundless.” It is a fantasy which must find a way of prevailing in spite of the obligatory subject matter handed the commercial artist-designer: the product and what the client wants to say about it. For, after all, to many of his employers, the commercial artist is no more than a hired hand, a paid “expresser”.

The best the serious commercial artist can do in such circumstances—and Paul Rand is exemplary in this respect—is to create with intensity, bringing to each assignment the full wealth of past experience and personal inventive goals. Thus armed, Paul Rand has inspired the general buying public—and especially young commercial artists—by creating art that makes companies look good. It is beyond his powers, or those of any other commercial artist, to make them do good, although the kind of work the Rands do for companies might even give the most hard-minded executives glimpses of the world of humanism that the true artist in habits, salutary for the executives and the consumers they hold in thrall.

But, of course, there’s more to it than that, especially in the fields of advertising art, or art for industry, where the man who supplies the money is waiting for the designer to show him that he, the designer, can sell the product, or at least help to sell it. Rand’s way of dealing with this fellow seems to be to say to him, in effect,

Don’t rush me; don’t get excited; I’ll show you that it can be done just as well, if not better, certainly not worse, with good design.

Thus, many a Rand client might receive a bit of design education. When I think of the skill and invention characteristic of Paul Rand’s work, I’m reminded of something that John Barth wrote recently: “I happen to prefer the kind of art that’s difficult to do.” Evidently Rand’s clients do, too.

The day I went to seen Rand’s recent one-man show at the IBM Gallery in New York, I realized that the public appreciates his work because of its simplicity, and the awareness that such simplicity is not easy to achieve. For examples, an illustration for Westinghouse ad reproduced here, shows a fishbowl, which is black halfway up to represent water, and light blue for the air above. In the water there are two little fishes—one red, one yellow— that a child could have cut out with scissors. But no child ever had the boldness and charm to use them for this purpose. Mies van der Rohe’s dictum “less is more” is exemplified by Rand’s cover for a Ford brochure illustrated in this article. Over a red tint block that bleeds off the sheet on all four sides that four-letter word FORD is printed in black: the F in the upper left corner, the O in the upper right corner, the R in the lower left corner, and the D in the lower right. Anyone might have thought of that, but no one had until now.

It is surprising how, while still maintaining close attention to the function of the ad, poster or package, Rand manages to project the influences of his fine-art mentors. These as everyone familiar with Rand’s work knows by now, are principally modern masters of fantasy, Miro and Klee. Miro seems echoed mainly in Rand’s use of solid color, a technique which Rand does not imitate Miro so much as show that he is a brother of the blood. The Klee influence seems apparent in Rand’s touch with pen or brush or typography, which is never aggressive, always subtle, always ready to take a walk with that line to Cockaigne and beyond.

Touch is one thing that distinguishes a man from a machine. Since Rand has done much work for IBM, he has faced a lot of questions about art and the computer. The larger question, he feels, is not whether the computer will change the course of art, but will the computer change the course of the development of man? Only man can decide. And I suppose you could say in the particular case of the computer’s influence on art itself, only the artist can decide. The computer, as far as the artist is concerned, is an extension of the hand. It’s true, you don’t touch paper or canvas with it as you do with brush or pen.…Meduim and content always affect each other. Content is a way of saying; medium is a way of answering back or vice versa. Of course, we can’t imagine art without both content and medium. Thoreau, when he heard that Maine and Texas could communicate by teleraph, wanted to know what Maine had to say to Texas.

Like other good professional graphic artists working in the commercial field, Rand is in full command of graphic techniques. He knows how to use the resources of photographs—photograms, montage, screened overlays—and he uses his own modest, graceful and straightforward handwriting frequently. In Rand’s business, the more of this sort of thing one has at one’s command the better, because the great variety of advertising messages the commercial artist must deal with calls for an ever-changing variety of voices and accents that must somehow find graphic expression.

It is useless now to reflect on what would have developed if Rand, instead of having become a commercial artists while still in his teens, had opted for fine-art. What advice would he offer to young people enterting art fields today? “How can you give advice to people you don’t know? I have trouble enough giving advice to people I know. I have trouble enough knowing the people I know, and I certainly have trouble knowing what the world, let alone the world of the arts, will be like as the new people go out to meet it.”

I wonder how the members of the once-over-lightly generation, some of whom Rand must have had to contend with at Yale, reacted to Rand’s relentlessness in the pursuit of excellence. Here is Rand’s advice to all prospective creators:

We shape our buildings, then our buildings shape us,’ said Mr. Churchill. So I guess all I can say is, be careful how you build as well as what you build. Or, as G.B. Shaw put it, we’re the only windows we have through which to look at the world, so we’d better keep ourselves clean and bright.

One thing is certain: no matter how successful Rand might have become as a fine artist, he would never have reached the vast audience he has reached, an audience that deserves better than it usually gets—that deserves more Paul Rands.