Estimated reading time: | Select text to share via Facebook, Twitter or Email

All knowledge is derived from and verified by direct intuitive observation.– A N. Whitehead 1

I HAVE ALWAYS FELT THAT INTUITIVE JUDGMENT IS, somehow, the source of all great ideas. But such judgment is intangible and offers little comfort for those in authority: in commerce, in education, or in the church. In addition, judgments that lack the support of research findings, group thinking, and task forces are generally suspect. Perhaps one of the reasons intuition has not won many popularity contests is that it is only vaguely understood, if at all. “What is this intuition?” said Henri Bergson. “If the philosopher has not been able to give the formula for it, we certainly are not able to do so.” [2]

The semantics of intuition are, for the most part, bewildering. One can perhaps understand intuition more easily by intuitive judgment than by definition, although “it is as rich in suggestion as poor in definition.” [3]

In its broadest sense, we are told, intuition means “immediate apprehension”. Immediate may be used to signify the absence of: inference, causes, symbols, thoughts, justification, or definition. Kant defines immediate: “without the mediation of concepts.” Apprehension, among others, may include such unrelated states as: sensation, knowledge, and mystical rapport. [4]

4. Immanuel Kant, Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Vol. IV, New York 1967, p. 204.

“Though the characteristics of knowing, of immediacy, of truth are all present, the quality which is especially present to the mind when using the word in any of these senses is that of inexplicability.” [5]

The dictionary tells us that intuition is a perception or view, immediate apprehension of truth or supposed truth, in the absence of conscious, rational processes. [6]

The OED equates intuition with unconscious dexterity or skill, and this is as simple a definition as one can possibly imagine. So, there is really no one definition for intuition. For the sake of this essay we can settle on: a flash of insight.

6. English Larousse, 1968.

Intuition cannot be willed or taught. It works in mysterious ways and has something in common with dreams. It has nothing to do with intentions, with pressing buttons, or with programming. It is something that just happens-an idea out of the blue-characterized sometimes by suddenness and surprise, with a feeling of elation, excitement, and a release of tension. Intuition is somehow related to experience, habit, native ability, religion, culture, imagination and education and, at some point, is no stranger to reason. “There is no antagonism between instinct and reason,” said William James. “Reason per se can inhibit no impulses … Reason may, however, make an inference which will excite the imagination so as to let loose the impulse the other way.” [7]

Herbert Spencer has this to say on the subject:

“There is no hiatus between instinct and reason … a rational action is simply an instinctive response which has survived in a struggle with other instinctive responses aroused by a situation; ‘deliberation’ is merely the internecine strife of rival impulses. At bottom, reason and instinct, and life, are one.”[8]

8. Herbert Spencer, Principles of Psychology, New York 1910, p. 453-455.

Intuition does not always generate great ideas. Getting into a bathtub and coming up with the idea of the displacement of water (Archimedes) is uncommon evidence of intuition. Most intuitive acts are uneventful daily activities. When great intuitive accomplishments are cited, they are usually the achievements of great men. “Newton could hold a problem in his mind for hours and days and weeks until it surrendered to him its secret. Then, being a supreme mathematical technician, he could dress it up how you will, for the purposes of exposition. But it was his intuition which was preeminently extraordinary …” [9]

The question is really less a matter of experiencing than of listening to one’s intuitions, of following rather than of dismissing them. It is also the quality of one’s intuitions-whether they are banal (as most are) or exciting (as very few are)-that matters.

“Behaving instinctively” declares B. F. Skinner, “in the sense of behaving as the effect of unanalyzed contingencies, is the very starting point of behavioristic analysis. A person is said to behave intuitively when he does not use reason. Instinct is sometimes a synonym: it is said to be a mistake to ‘attribute to logical design what is the result of blind instinct,’ but the reference is simply to behavior shaped by unanalyzed contingencies of reinforcement. The blind instinct of the artist is the effect of the idiosyncratic consequences of his work. It is no ’betrayal of reason’ to accept what artists teach us about life, nature, and society, since not to accept it would be to assert that contingencies are effective only when they have been described or formulated as rules.” sup [10]

The words intuition, instinct, impulse, hunch, insight, as used in this paper, are interchangeable. Instincts, however, are commonly understood to refer to lower animals, and intuition to man.

The ability to intuit is not reserved for any special class of individuals: painters, writers, designers, dancers, or musicians, many of whom believe that this ability is something special, something God-given. The intuitive faculty, though, seems more pervasive in matters of aesthetics than in matters of daily routine. Except in a most general sense, one cannot prove the validity of color, contrast, texture, or shape. Compliance with all the laws and systems of form, of restraint, of proportion will not provide proof for the soundness of a work of art, nor guarantee its coming to fruition. This is one of the reasons it is so difficult to understand or teach art, and why countless books on art are mere inventories, but not meaningful or really useful explanations. Even the rare instances of brilliant exposition by historians like Roger Fry, Malraux, or Wittkauer, however inspirational, however compelling, cannot directly generate great or even good works.

Without regard to available systems, e.g. The Golden Section, DIN proportions, typographic grids, the designer works intuitively. This is something about which one is often confused. No system of proportion, color, or space can possibly insure meaningful results. A system can be applied either intuitively or consciously, interestingly or boringly. There is always an element of choice, sometimes called good judgment, at other times good taste. Aside from practical considerations, in matters of form the typographer, for example, must rely on intuition. How else does one select a typeface, decide on its size, line width, leading, and format? The alternatives are to repeat one’s previous performances, to imitate what others have done, or simply to make arbitrary decisions.

The resentment that creative people have against such things as research, it seems to me, is largely the resentment of those who made decision intuitively, without the “benefit” or interference of so-called reasonable arguments. Opinion polls, in which intuition most likely plays some role, are, ironically, often used to combat the notions of creative designers and writers whose efforts are, by and large, intuitive. It is fairly safe to speculate that most good ideas in the field of communication take shape in this manner. Nor would it be wrong to assume that some of the best ideas in any field are in some way, at some point, intuitively perceived. “Think Small”, so effectively exploited in VW advertisements seems, unquestionably, an ingenious idea intuitively generated. It is a contradictory statement that evokes its opposite: Think Big. Such a statement, like Mies van de Rohe’s “less is more” is similarly effective because it involves the spectator’s sense of irony.

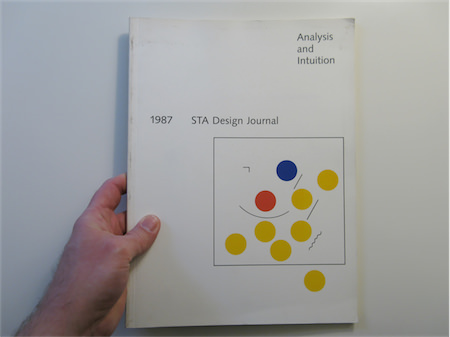

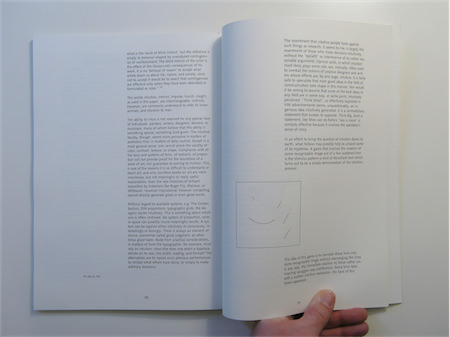

In an effort to bring the question of intuition down to earth, what follows may possibly help to unravel some of its mysteries. A game that involves the creation of some recognizable image out of a few scattered lines is the stimulus pattern-a kind of Rorschach test-which turns out to be a simple demonstration of the intuitive process:

The idea of this game is to translate these lines into some recognizable image without rearranging the lines in any way. My immediate reaction to these rather uninspiring squiggles was indifference. Some time later, with a sudden intuitive realization, the face of this clown appeared:

The solution demonstrated how it is possible to transform a few meaningless lines into a lively image, how to achieve interest where there is no interest. The designer is constantly confronting such everyday perplexities. Here is a lesson in contrasts: black lines, colored dots (red, yellow, blue). By juxtaposition these elements are transformed into a lively abstraction as well as the suggestion of a clown. It is possible, of course, for the facial features to be more descriptive, merely by adding a little triangular cap, but simplicity and restraint are equally, if not more, important-a lesson, not only in economy, but in appropriateness to a particular problem.

This same problem was later assigned to a class of design students. No specifications were given other than, “Try making something out of these lines,” nor were the words “recognizable image” used. There was no reference to rearrangement of lines, although one student did manage to alter the grouping. The object of this exercise was not a question of right or wrong, but an indication of a way of thinking.

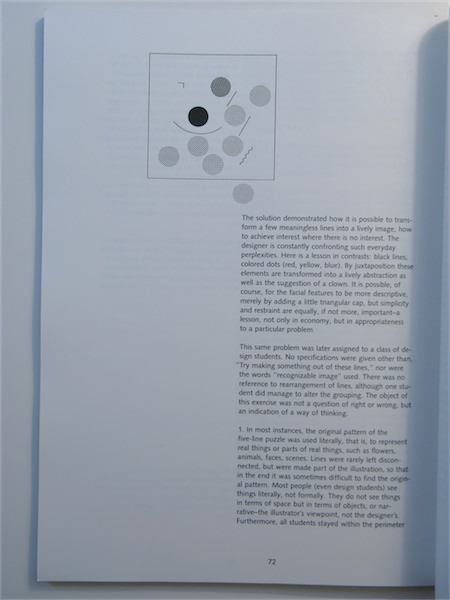

1.

In most instances, the original pattern of the five-line puzzle was used literally, that is, to represent real things or parts of real things, such as flowers, animals, faces, scenes. Lines were rarely left disconnected, but were made part of the illustration, so that in the end it was sometimes difficult to find the original pattern. Most people (even design students) see things literally, not formally. They do not see things in terms of space but in terms of objects, or narrative-the illustrator’s viewpoint, not the designer’s.

Furthermore, all students stayed within the perimeter and did not venture outside the square. Nor did any of the students use color-intuitively, self imposed restrictions.

2.

In only one instance was the segment of a circle used to illustrate a smiling face. Intuitively this was rejected by roughly 50% of the class as being too obvious and therefore unimaginative and bound to be copied by others. Interestingly enough, when intuition is strong enough, it even pushes reason aside. “A loyalty to his intuitive view of things and a voluntary submission to its authority” said Jung, dealing with the question of inhibitions in creative thinking. [11]

3.

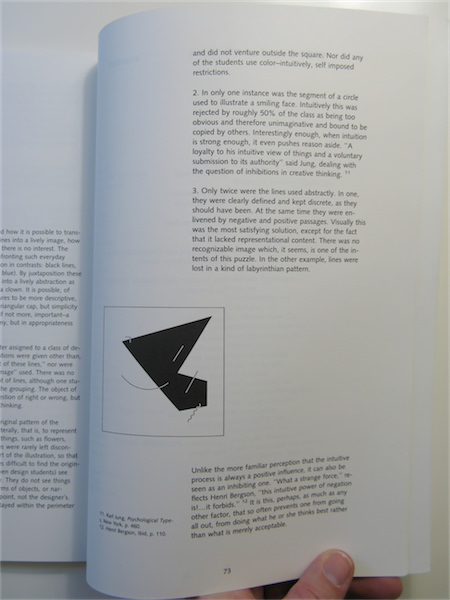

Only twice were the lines used abstractly. In one, they were clearly defined and kept discrete, as they should have been. At the same time they were enlivened by negative and positive passages. Visually this was the most satisfying solution, except for the fact that it lacked representational content. There was no recognizable image which, it seems, is one of the intents of this puzzle. In the other example, lines were lost in a kind of labyrinthian pattern.

Unlike the more familiar perception that the intuitive process is a ways a positive influence, it can also be see as an inhibiting one. “What a strange force,” reflects Henri Bergson, “this intuitive power of negation is! …it forbids.”[12]

It is this, perhaps, as much as any other factor, that so often prevents one from going all out, from doing what he or she thinks best rather than what is merely acceptable.

Paul Rand’s vast experience has included magazine and advertising art direction, packaging, book illustration, and typography, as well as painting and art education. He has taught at Pratt Institute and Cooper Union, and since 1956 has been a professor of graphic design at Yale University. He has been honored with prestigious awards from many professional and academic groups. Among the many clients for whom he has been consultant and/or designer are The American Broadcasting Company, Cummins Engine Company, IBM Corporation, and Westinghouse Electric Corporation. He is the author of Paul Rand: A Designer’s Art.