TM offers graphic designers and those interested in the history of design and branding a uniquely detailed look at a select group of the very best visual identities.

The book takes 29 internationally recognized logos and explains their development, design, usage, and purpose. Based upon interviews with the designers responsible for these totems, and encompassing the marks from a range of corporate, artistic, and cultural institutions from across the globe, TM reveals the stories behind such icons as the Coca-Cola logotype, the Penguin Books’ colophon, and the Michelin Man.

Based upon comprehensive research, authoritatively written and including a wealth of archival images, TM is an opportunity to discover how designers are able to squeeze entire identities into 29 simple logos.

The Original Text

By Mark Sinclair

The string-bound package at the top of Paul Rand’s 1961 United Parcel Service logo was a cause for concern for some at the company. It was felt that the designer’s dependence on string as a graphic device ran counter to UPS’s discouragement of its use on packages. Rand argued that his bow-tie element was the only way a rectangular shape could be made to represent a parcel, and that it was a simple, immediately recognizable graphic clue to what the company did. It was perhaps even an emotive gesture: as well as simply delivering packages to people, UPS delivered gifts.

Rand famously claimed that the decision to use this simple communicative element was sealed when he showed it to his family. ‘I have always believed that if I could understand my own work, anybody could,’ he claimed in an interview with design historian Steven Heller. ‘I use myself as a measure, but I also use other people - not experts or professionals. My daughter, for example, was seven when I showed her a sketch for the United Parcel Service logo. I asked her what it looked like, and she said, “That’s a present, Daddy.” You couldn’t have rehearsed it any better.’

When Rand’s design was chosen to be the company’s new logo, a shield device had represented the organization since 1916. And until 1937 the symbol had even featured a parcel tied up with string with the words ‘Safe Swift Sure’ written on an accompanying label, the itself grasped by a flying eagle. Seen in this light, Rand’s design was at the very least a refinement of the company’s original visual message. Yet the astuteness of his logo was in making the parcel element part of the shield (or escutcheon, as Rand would have it), not merely an add-on. By making this graphic inseparable from the whole design, the logo retained a solidity, despite featuring a seemingly playful, even sentimental, gesture.

For Rand, including something witty in his final design was often an intention at the outset of a project. ‘Humour is another goal I have always steered toward in my work,’ he told Heller. ‘People who don’t have a sense of humour are a drag. Interesting people are humorous, one way or another.’ In this respect, as a designer, Rand was deadly serious about being funny. He elaborated on the subject in his book A Designer’s Art. ‘The visual message which professes to be profound or elegant often boomerangs as mere pretension,’ he wrote, ‘and the frame of mind that looks at humour as trivial and flighty mistakes the shadow for the substance. In short, the notion that the humorous approach to visual communication is undignified or belittling is sheer nonsense.’ The parcel atop the UPS shield would amuse people. By making them smile, UPS had a better chance of people remembering the logo and what it stood for.

Rand’s own design output had embraced logo and identity design in the 1950s. ‘While designing a logo is somewhat analogous to any kind of design problem, it’s special,’ he later claimed. ‘The problems are different from those in advertising. You have to break everything down into the smallest possible denominator. You’re not selling a product, so you don’t have to persuade anybody except the client.’

For UPS, Rand was one of five professional designers and a handful of company employees who submitted proposals for a new design in the early 1960s. As UPS’s in-house magazine Big Idea claimed at the time, the company’s previous logo was ‘still very appropriate for our retail operation but does not cover our newer wholesale service. What we needed was an emblem that would tell the whole story … wholesale as well as retail.’ The shield, it was felt, both linked with the organization’s heritage and was a familiar, easily identifiable symbol of dignity and strength. When Rand’s shield design was chosen, it was decided it would be displayed on UPS’s fleet of vehicles in gold against brown or black backgrounds.

In the article that introduced the new look, it was also suggested that the logo was to be applied with some degree of understatement. It needed to be subtle so as not to compete with the thousands of other company logos displayed on the packages that UPS would be delivering across the country. ‘UPS has tried to remain inconspicuous in the design and display of its trademark,’ ran the editorial. ‘However, the very fact that the other companies [via the packages that UPS delivered] attempt to be overwhelming in their advertising makes UPS conspicuous in its inconspicuousness. Which, after all, is exactly the effect UPS wanted.’

Whether any design of his could last was a matter that Rand addressed in his interview with Heller. ‘A good solution, in addition to being right, should have the potential for longevity,’ he said. ‘Yet I don’t think one can design for permanence. One designs for function, for usefulness, rightness, beauty. Permanence is up to God.’ But Rand’s work for UPS did last - and when in 2003 the parcel device was finally retired in a design overhaul by FutureBrand, the change was met with some derision. Many knocked the addition of trendy gradients to render the shield in a slicker 3D design, while others were just saddened to see the famous parcel taken out of service. For UPS, the new logo symbolized the company’s expansion from package delivery into a broader range of services - a bow-tied parcel no longer reflected its aims and the realities of its business. In fact, in 1991, in a piece written for the AIGA (American Institute of Graphic Arts), Rand had hinted that he had ‘not long ago’ offered to ‘make some minor adjustments to the UPS logo’ but that ‘this offer was unceremoniously turned down, even though compensation played no role’. It is futile - but not without interest - to wonder what Rand would have altered nearly 30 years after creating his original design. The typeface? The parcel? The divisive string? Up until 2003, though, UPS must have felt that Rand’s shield was still strong enough to do its Job.

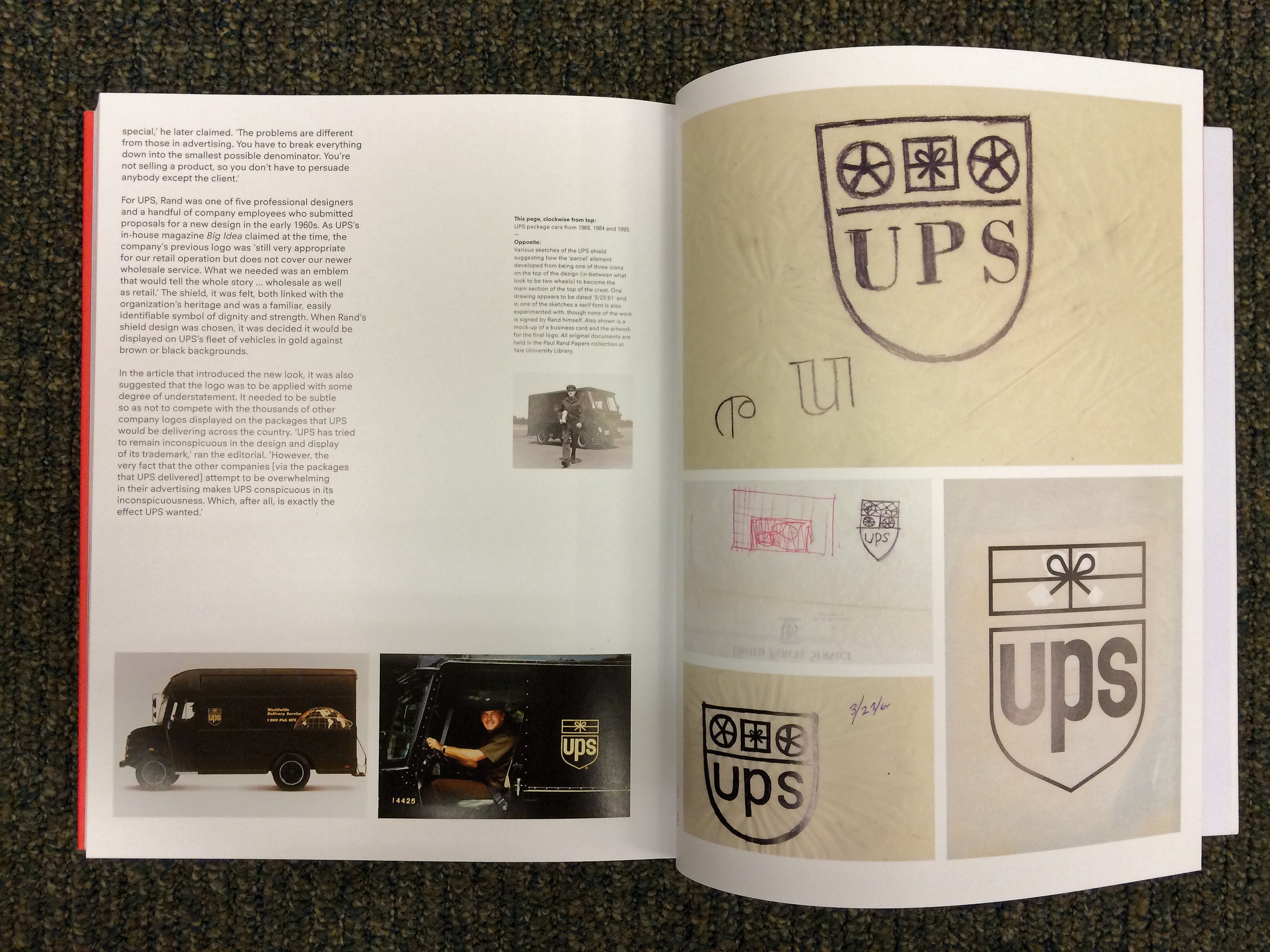

This page, clockwise from top: UPS package cars from 1968, 1984 and 1993.

Opposite: Various sketches of the UPS shield suggesting how the ‘parcel’ element developed from being one of three icons on the top of the design (in-between what look to be two wheels) to become the main section of the top of the crest. One drawing appears to be dated ‘3/23/61’ and in one of the sketches a serif font is also experimented with, though none of the work is signed by Rand himself. Also shown is a mock-up of a business card and the artwork for the final logo. All original documents are held in the Paul Rand Papers collection at Yale University Library.

Opposite, clockwise from top: Aircraft displaying UPS livery at Louisville airport, Kentucky, 1988. UPS driver with Next Day Air envelopes in front of a UPS aircraft. A German UPS delivery cart, 1990.

Below: UPS package cars, 1971.