To men of former ages, the meaning of life was, so to speak, “given,” in part by the relatively unambiguous definition of the individual’s vocational role. Clearly, life has meaning for man not only in terms of goals but also in terms of his doing, his functioning as a productive human being. If the artist fails to find goals or cannot manage to function within the cultural climate, not only is his art “foredoomed” but so is he. Precariously perched between economics and aesthetics, his performance judged by the grimly impersonal yet arbitrary “Does it sell?” the commercial artist has great difficult in finding his artistic personality, let alone asserting it. But art has often been practiced under severe constraints, whether those of the community, the church, or the individual patron. Under almost any conditions, short of absolute tyranny, art usually manages to prevail. Even if Lorenzo de’ Medici had hated art, it is hard to imagine that Michelangelo would not have found some way to make sculpture and to paint. The artist—easel painter or designer—if he is genuinely committed to his vocation, does not need to be given a reason for existence: he is himself the reason.

Unfortunately he does not always recognize this fact. There are those who believe that the role the designer must play is fixed and determined by the socioeconomic climate. He must discover his functional niche and fit himself into it. I would suggest that this ready-made image ignores the part the artist (or for that matter the carpenter or housewife) plays in creating the socio-economic climate. This creative contribution is made by everybody, willy-nilly, but it can become a far more significant one if the individual is aware that he is making it.

Such awareness, furthermore, is a basic source of that human dignity and pride which are prerequisite for the artist’s attainment of creative status. The individual who feels himself a hapless, helpless pawn in some obscure life game obviously has trouble believing in either himself or the worth of his endeavor. Unquestionably, as men or artists, we must be able to adapt ourselves to environmental conditions, but we can do this only within certain limits. I would say that an understanding of man’s intrinsic needs, and of the necessity to search for a climate in which those needs could be realized is fundamental to the education of the designer. Whether as advertising tycoons, missile builders, public or private citizens, we are all men, and to endure we must be first of all for ourselves. It is only when man (and the hordes of individuals that term stands for) is not accepted as the center of human concern that it becomes feasible to create a system of production which values profit out of proportion to responsible public service, or to design ads in which the only aesthetic criterion is “How sexy is the girl?”

If the popular artist is confronted too fast by too much, is split, is high-pressured, and is a part ofa morally confused and aesthetically apathetic society, it is simple enough to say he can do something about it—but the bigger question is how.

First of all, perhaps, he must try to see the environment and himself in relation to it as objectively as possible. This is not easy. Where the “I” is involved, either specifically or generically, all kinds of resistances are aroused. It is much simpler and often more agreeable to see ourselves and the world through pastel-colored glasses. But if the artist does tumble into the swirling sea of confusion that surrounds his small island of individuality, he can at best only keep his head above water—certainly he will not be able to direct his course. He will no longer have a chance to develop the independence of thought necessary for making valid judgments and decisions.

If he can think independently and logically, the popular artist may come to see continuous and accelerating change, not as confusion compounded, but as the present form of stability. He may also be able to distinguish between the appearance of change and true change.

For the commercial artist such a distinction is vital. As a product designer he is increasingly required to consider what has been called “the newness factor;” as an advertising designer he is told by the copywriter that the resultant product is New! Amazing! Different! The First Time in History! All too often this “newness” has nothing to do with the innovation that is genuine change—an invention or an original method of doing or a mode of seeing and thinking. “Newness” frequently consists of contrived and transitory surprise effects such as pink stoves, automobile fins, graphic tricks. The novelty-for-novelty’s-sake boom, with its concomitants of hypocrisy, superficiality, and waste, corrupts the designer who is taken in by them.

The differentiation of fact from fiction gives the commercial artist a basis for the far-reachjng decisions he must often make. It is because of his relationship to industry that these decisions have effects far beyond the immediate aesthetic ones. When the artist designs a product, not only are millions of industry’s dollars risked, but so are the jobs of those people involved making the product. Even the graphic artist by “selling” a product helps secure jobs as well as profits. Under these circumstances it becomes a matter of social responsibility for the commercial artist to have a clear and firm understanding of what he is doing and why.

The profession or job of the artist in the commercial field is clear. He must design a product that will sell, or create a visual work that will help sell, a product, a process, or a service. At the same time, if he has both talent and a commitment to aesthetic values, he will automatically try to make the product or graphic design both pleasing and visually stimulating to the user or viewer. By stimulating I mean that his work will add something to the consumer’s experience.

While there is absolutely no question that talent is far and away the most important attribute of any artist, it is also true that if this talent is not backed by conviction of purpose, it may never be effectively exercised. The sincere artist needs not only the moral support that his belief in his work as an aesthetic statement gives him, but also the support that an understanding of his general role in society can give him. It is this role that justifies his spending the client’s money and his risking other people’s jobs, and it entitles him to make mistakes. Both through his work and through the personal statement of his existence he adds something to the world: he gives it new ways of feeling and of thinking, he opens doors to new experience, he provides new alternatives as solutions to old problems.

Like any other art, popular art relates formal and material elements. The material elements may be of a special nature, but, as in all art, the material and the formal are fused by an idea. Such ideas come originally from the artist’s conscious and unconscious experience of the world around him. The experience that can give rise to these ideas is of a special kind. As Joyce Carey says, “The artist, painter, writer, or composer starts always with an experience that is a kind of discovery. He comes upon it with the sense of a discovery; in fact, it is truer to say that it comes upon him as a discovery.”[1] This is reminiscent of Picasso’s admonition not to seek but to find. What both men are saying is that the very act of experiencing is for the artist a creative act; he must bring enough to the experience for it lead him to a discovery about its nature, a discovery he will try to embody and transmit in a work of art. Surfeited by sensory stimuli, the artist today will be helpless to convert experience into ideas if he cannot select, organize, and deeply feel his experiences.

1 Joyce Carey, Art and Reality (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1958), p. 1

Ideas do not need to be esoteric to be original or exciting. As H. L. Mencken says of Shaw’s plays, “The roots of each one of them are in platitude; the roots of every effective stage play are in platitude.” And when he asks why Shaw is able to “kick up such a pother?” he answers, “For the simplest of reasons. Because he practices with great zest and skill the fine art of exhibiting the obvious in unexpected and terrifying lights.”[2] What Cezanne did with apples or Picasso with guitars makes it quite clear that revelation does not depend upon complication. In 1947 I wrote what I still hold to be true, “The problem of the artist is to make the commonplace uncommonplace.”[3]

2 H. L. Mencken, Prejudices: A Selection (New York: Vintage K58,Alfred A. Knopf, 1958), pp. 27 and 28.

3 Paul Rand, Thoughts on Design (New York: George Wittenborn, Inc., 1947), p. 53.

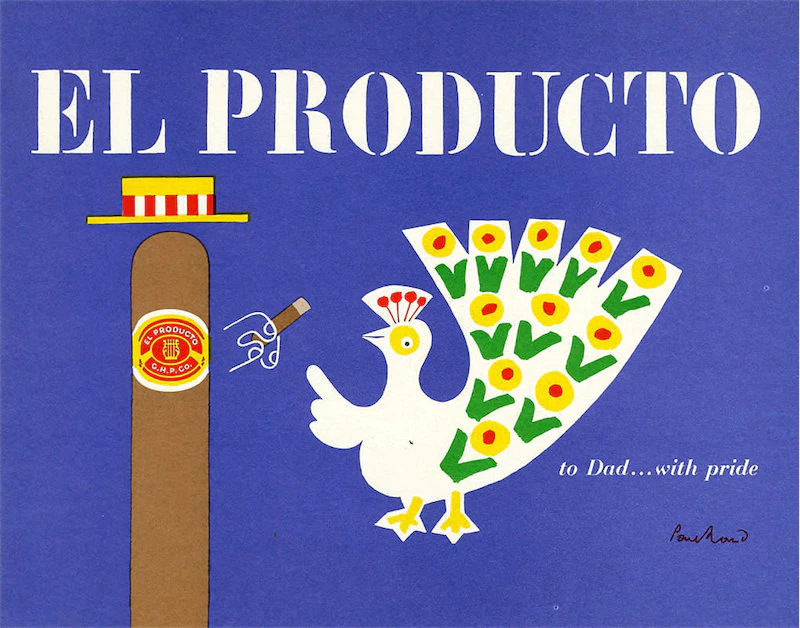

If artistic quality depended on exalted subject matter, the commercial artist, as well as the advertising agency and advertiser, would be in a bad way. For a number of years I have worked with a cigarmanufacturing company whose product, visually, is not in itself unusual. A cigar is almost as commonplace as an apple, but if I fail to make ads for cigars that are lively and original, it will not be the cigar that is at fault.

What is important about visual ideas is that they express the artist’s experience and opinions in such a way that he communicates them to others, and that they, in turn, feel a sense of discovery on seeing the work, a sense similar to the artist’s own. Only this can enrich the spectator’s personal experience. Further, in the case of the graphic artist, these ideas must be so conceived as to help sell the product.

The artist is certainly not alone in facing these problems: they confront the businessman, the scientist, and the technologist. Nor is he alone in his creative drive. The popular artist who sees the world as dominated by mechanistic thinking run amuck, and himself as the machine’s victim, feels powerless and alienated. This is unrealistic. The creative, the imaginative, even the aesthetic nature of science is now widely recognized.

If there is reassurance for both artist and scientist in the recognition of this similarity, there is actual danger in the ignoring of it. The mechanistic view of the world saw society as governed by laws similar to what were then believed to be the absolute and immutable “laws” of natural science. It tended to divorce social forces from the actions and decisions of man. The continued popularity of such an attitude is to my mind far more menacing than the physical achievements of science and technology. It is my belief that if we are at the mercy of “social forces,” it is because we have put ourselves there. If we have become, or are becoming, “slaves of the machine,” it means that we have acceded to slavery.

Even in the astonishing world of the computer and the simulation machine, it must be remembered that, at least initially, it is we who will give them a program. The kind of service they render depends on our decisions, on what we think (given their capacities) they ought to do. The key problem is not with machine or with technology in general, it is with the “ought.” For both scientist and artist, as well as the industry that brings them together, it is a matter of over-all aims, specific purposes, and values. It is up to us to decide what we want.

Perception — how we see something — is always conditioned by what we are looking for, and why. In this way we are always faced with questions of value. A turbine must be “scientifically” designed in order to operate, but to design it at all was at one time a matter of decision. Such decisions mayor may not be based on needs, but they are surely based on wants. Products do not have to be beautifully designed. Things can be made and marketed without our considering their aesthetic aspects, ads can convince without pleasing or heightening the spectator’s visual awareness. But should they? The world of business could, at least for a while, function without benefit of art—but should it? I think not, if only for the simple reason that the world would be a poorer place if it did.

The very raison d’etre of the commercial artist, namely, to help sell products and services, is often cited by him as the reason he cannot do good work. To my mind, this attitude is just as often the culprit as is the basic nature of the work. The commercial artist may feel inferior and therefore on the defensive with respect to the fine arts. There is undoubtedly a great and real difference between so-called fine art and commercial art, namely, a difference in purpose—a fact that must be recognized and accepted. But there is nothing wrong or shameful in selling. The shame and wrong come in only if the artist designs products or ads that do not meet his standards of artistic integrity.

The lament of the popular artist that he is not permitted to do good work because good work is neither wanted nor understood by his employers is universal. It is very often true. But if the artist honestly evaluates his work and that of the other complainers, he will frequently find that the “good work” the businessman has rejected is not actually so “good.” The client can be right: the artist can be self-righteous. In accusing the businessman of being “antimodern” the artist is often justified. But many times “it’s too modern” simply means that the client does not know what he is really objecting to. Unbeknown to himself, the client may be reacting to excessive streamlining, an inappropriate symbol, poor typography, or a genuinely inadequate display of the product. The artist must, without bias, sincerely try to interpret these reactions.

If there is nothing wrong with selling, even with “hard” selling, there is one type that is wrong: rpisrepresentative selling. Morally, it is very difficult for an artist to do a direct and creative job if dishonest claims are being made for the product he is asked to advertise, or if, as an industrial designer, he is supposed to exercise mere stylistic ingenuity to give an old product a new appearance. The artist’s sense of worth depends on his feeling of integrity. If this is destroyed, he will no longer be able to function creatively.

On the other hand, it is surely more consoling to the commercial artist to see himself betrayed by the shortsightedness of commerce or to believe he is forced to submit to “what the public wants” than to think he himself may be at fault. The artist does not wish to see himself as either so indifferent to quality or so cowed by economic factors that he has taken the easy way out—just do what the boss says, and maybe give it a new twist. Yet actually it may not always be the lack of taste on the part of client and public that accounts for bad work, but the artist’s own lack of courage.

To do work of integrity the artist must have the courage to fight for what he believes. This bravery may never earn him a medal, and it must be undertaken in the face of a danger that has no element of high adventure in it—the cold, hard possibility of losing his job.Yet the courage of his convictions is, along with his talent, his only source of strength. The businessman will never respect the professional who does not believe in what he does. The businessman under these circumstances can only “use” the artist for his own ends—and why not, if the artist himself has no ends? As long as he remains “useful,” the artist will keep his job, but he will lose his self-respect and eventually give up being an artist, except, perhaps, wistfully on Sundays.

In asking the artist to have courage, we must ask the same of industry. The impetus to conform, so widespread today, will, if not checked, kill all forms of creativity. In the world of commercial art, conformism is expressed, for example, by the tenacious timidity with which advertisers cling to the bald presentation of sex, sentimentality, and snobbism, and by such phenomena as the sudden blossoming of fins on virtually all makes of American cars. The artist knows he must fight conformity, but it is a battle he cannot win alone.

Business has a strong tendency to wait for a few brave pioneers to produce or underwrite original work, then rush to climb on the bandwagon—and the artist follows. The bandwagon, of course, may not even be going in the right direction. For instance, the attention and admiration evoked by the high caliber of Container Corporation’s advertising have induced many an advertiser to say, “Let’s do something like Container,” without considering that it might not be at all suited to his needs. Specific problems require specific visual solutions. This does not mean that an advertisement for a soap manufacturer and one for Container Corporation cannot have much in common, or that a toaster cannot be designed in terms of the same sound principles as a carpenter’s hammer. Both ads and both products can be made to fulfill their functions and also to be aesthetically gratifying; both can express respect for and concern with the broadest interests of the consumer.

It is unfortunately rare that the commercial artist and his employer, be it industry or advertising agency, work together in an atmosphere of mutual understanding and cooperation. Against the outstanding achievements in design made possible by such companies as Olivetti, Container Corporation, IBM, CBS, El Producto Cigar Company, CIBA, and a comparatively few others, there stands the great dismal mountain of average work. The lack of confidence that industry in general evinces for creative talent and creative work is the most serious obstacle to raising the standards of popular art. Business pays well for the services of artists who are already recognized and are consequently “successful.” Success is a perfectly legitimate reward for competence and integrity, but if it is a precondition for acceptance, it leaves the beginner and the hitherto unrecognized innovator in an economic cul-de-sac

. Moreover, when business merely asks for something just “a little bit better” or “a little bit different,” it may well inhibit not only artistic creativity, but also all forms of creativity, scientific and technological included.

From a long-range standpoint, the interests of business and art are not opposed. The former could perhaps survive without the latter, for a time; but art is a vital form of that creative activity which makes any kind of growth possible. We are deluged with speeches, articles, books, and slogans warning us that our very survival as free nations depends on growth and progress—economic, scientific, technological. The kind of climate that fosters original work represents an over-all attitude, a general commitment to values that uphold and encourage the artist as well as the scientist and the businessman.