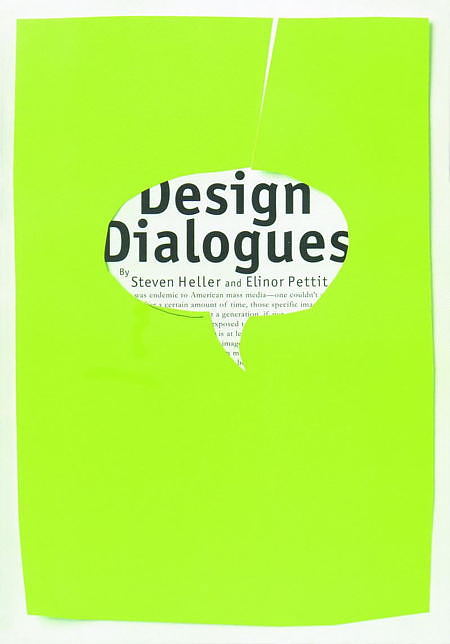

This wide-ranging compilation of interviews offers a colorful and candid introduction to the personalities, passions, and work of thirty-four respected designers, artists, authors, and media producers.

With design as the common thread, each exchange opens an individual perspective on the visual culture at large, ranging in focus from the manipulative power of images to the place of theory in design practice to the myriad interactions between design and life. The stories are woven from experiences in media, theory, history, politics, and the blurry realm of interactivity, and are told by such notables as Ellen Lupton discussing her life as a design curator, Tibor Kalman confronting the relationship between practice and social responsibility, John Plunkett on his motivations for founding Wired magazine, and Ralph Ginzburg telling all about the controversial publication that ultimately sent him to prison. Both an oral history of graphic design and a living record of where we are today, these engaging and evocative dialogues provide anyone interested in design or popular culture with a means of understanding, as well as ideas for working in, the visual world around them.

Included are thirty-four black-and-white illustrations and interviews with:

- Massimo Vignelli

- Paul Rand

- Stephen Doyle

- Jonathan Barnbrook

- Jonathan Hoefler

- Michael Ian Kaye

- Dana Arnett

- Chris Pullman

- Jose Conde

- Nicholas Callaway

- George Lois

- Philip Meggs

- Rick Prelinger

- Dan Solo

- Rick Poynor

- Ellen Lupton

- Katherine McCoy

- Johanna Drucker

- Ivan Chermayeff

- Milton Glaser

- Michael Bierut

- Sue Coe

- Stuart Ewen

- Ralph Ginzburg

- Tibor Kalman

- Richard Saul Wurman

- Michael Ray Charles

- Morris Wyszogrod

- Jules Feiffer

- Rodney Alan Greenblat

- David Vogler

- Edwin Schlossberg

- Robert Greenberg

- and John Plunkett.

The Original Text

By Steven Heller

PAUL RAND WAS AMERICA’S LEADING modern graphic designer in the disciplines of advertising, book, and corporate design. He studied at Parsons School of Design, Pratt Institute, and the Art Students League (where George Grosz was his teacher), all in New York City, but was primarily self-taught in the ways of modernism. In the early 1930s, he became a devoted follower of the European moderns and employed their economical and functional methods in his editorial design for Esquire and Apparel Arts. In 1941, he joined the William H. Weintraub Advertising Agency as its chief art director and proceeded to change the look and feel of American advertising, introducing a unique blend of wit, humor, and art-based aesthetics for massmarket clients. A master of many disciplines, he moved from editorial and advertising to corporate and packaging design, creating identities for IBM, Westinghouse, Cummins Engine, NeXT, Enron, and USSB. He is the author of three books, Paul Rand: A Designer’s Art (Yale, 1985), Design, Form, and Chaos (Yale. 1993), and From Lascaux to Brooklyn (Yale, 1996). He passed away in 1996. This interview was conducted in 1990.

— Steven Heller

STEVEN HELLER: What is the play instinct?

PAUL RAND: It is the instinct for order, the need for rules that, if broken, spoil the game, create uncertainty and irresolution. “Play is tense,” says Johan Huizinga. “It is the element of tension and solution that governs all solitary games of skill.” Without play, there would be no Picasso. Without play, there is no experimentation. Experimentation is the quest for answers.

SH: You design as though you were playing a game or piecing together a puzzle. Why don’t you just settle on a formula and follow it through to its logical conclusion?

PR: There are no formulas in creative work. I do many variations, which is a question of curiosity. I arrive at many different configurations-some just slight variations, others more radical-of an original idea. It is a game of evolution.

SH: Then, the play instinct is endemic to all design?

PR: There can be design without play, but that’s design without ideas. You talk to me as if I were a psychologist. I can speak only for myself. Play requires time to make the rules. All rules are custom-made to suit a special kind of game. In an environment in which time is money, one has no time to play. One must grasp at every straw. One is inhibited, and there is little time to create the conditions of play.

SH: Is there a difference between play and, say, work?

PR: I use the term “play,” but I mean coping with the problems of form and content, weighing relationships, establishing priorities. Every problem of form and content is different, which dictates that the rules of the game are different, too.

SH: Is play humor? Or do the two have different meanings?

PR: Not necessarily. It is one way of working. Its product may be very serious even if its spirit is humorous. I think of Picasso. His famous Bull’s Head, made up of a bicycle seat and handlebars transformed into the head of a bull, is certainly play and humor. It’s curious, a visual pun. Picasso is almost always humorous-but this does not rule out seriousness when he creates images that are contrary to what one would expect. He might put a fish in a birdcage, or a Rower with little bulls climbing up the stem. The notion of taking things out of context and giving them new meanings is inherently funny. My friend Shigeo Fukuda, the Japanese designer, is a good candidate for one whose sense of play is pertinent. Almost all of his work is the product of playfulness.

SH: You’ve discussed play as experimentation. Would you also describe play as doing things unwittingly?

PR: I don’t think that play is done unwittingly. At any rate, one doesn’t dwell over whether it’s play or something more serious-one just does it. Why does one want to see something rendered in many different ways? Why does one prefer to see a solution in different color combinations or in different techniques? That is an aspect of the play instinct, although it may also be a kind of satisfaction in being prolific. Still, most of the time, many variations provide a good reason to be confused and indiscriminate. I often have to stand away from a project for a while and return in a few weeks.

SH: As a painter one can do that, but as a designer do you have the time?

PR: Sure, I do it. Sometimes I find what’s wrong on that second look. But most of the time the work gets printed, and then I see my mistakes. Sometimes I’m able to catch it by having a job reprinted, paying for it myself, or, if the client is generous, getting him to do it. A good example of this is the UPS logo. I recently had an interview with a public relations person from UPS about the thirtieth anniversary of the logo. I said that I would like to correct the drawing because some wings ought to be changed. I added that I was certain the company would not approve any changes. She tried; regrettably, I was right.

SH: What’s wrong with the logo? It’s recognizable, aesthetically pleasing, and distinctively witty compared to the logos of the other package carriers.

PR: Aesthetically pleasing is not aesthetically perfect. There are two problems: one is that the configuration of the bow is unharmonious with the letterform; the other is that the counter of the p is incompatible with the other two letters.

SH: But the bow makes it a playful logo.

PR: Of course it does. In fact, the idea of taking something that’s traditionally seen as sacred, the shield, and sort of poking fun at it-which I’m doing by sticking a box on top of it is a seemingly frivolous gesture. The client, however, never considered it that way, and as it turned out the logo is meaningful because of that lighthearted intent. But that’s not the issue. The bow is drawn freely. Today I would use a compass.

SH: Isn’t the fact that it is freehand what gives it the needed light touch?

PR: Whether a drawing is done with or without the benefit of a tool-the compass-is unimportant. The spirit and intent are what counts. It would be more consistent to construct it geometrically, as are the shield and letters. All elements would be consistent and no one would be the wiser.

SH: For most corporations, their logo is sacrosanct and not meant to be an object of or for humor.

PR: Most corporations think the logo is a kind of rabbit’s foot or talisman-although sometimes it can be an albatross-and believe that if it is altered, something terrible will happen.

SH: Along those lines, you’ve designed some of the most recognizable logos in America, specifically the one for IBM. Years later, after you showed how this logo could be applied, you designed a poster that showed the I as an eye, the B as a bee, and the M as itself. You said that the company didn’t publish it until later. Was that because it poked fun at the company?

PR: They thought that it might encourage people working for IBM to misuse or misinterpret the logo. Later, though, they changed their minds because it didn’t become the license they anticipated. What I did turned out to be a humorous idea; in fact, virtually any rebus is a humorous vehicle. Look at the rebuses of Lewis Carroll. A rebus is a form of dramatization making an idea more memorable.

SH: You design as though you were playing a game or piecing together a puzzle. Why don’t you just settle on a formula and follow it through to its logical conclusion?

PR: There are no formulas in creative work. I do many variations, which is a question of curiosity. I arrive at many different configurations-some just slight variations, others more radical-of an original idea. It is a game of evolution.

SH: When you begin a project, regardless of medium, are you playing with forms?

PR: I don’t just play around with form or forms. That implies a paucity of ideas. I always start with an idea, otherwise I’m working with mere abstractions. It’s like taking a trip without a destination. Form develops an idea. You see, form is the manipulation of ideas-or content, if you prefer. And that’s exactly what designers are, manipulators of content.

SH: Do you intentionally try to create humorous ideas?

PR: No. There are designers with a sense of humor and there are those without. Given the same content, the success is in the delivery. Groucho Marx can make anything funny, while others with similar material might just be tiresome. Still, something can be funny without being humorous-with irony. It helps, of course, if the material is amusing, but someone with a sense of humor can make almost anything funny. How something is done or delivered is often more important than what.

SH: One of your jackets, for a book called Leave Cancelled, comes to mind in this regard, It shows a classical figure flying on a pink background with a number of die-cut bullet holes through the paper.

PR: I wouldn’t call that funny. The image is Eros, the god of love. That’s not inherently funny. The bullet holes have to do with the plot; the protagonist has to return to his regiment before his date is over. Rather than funny, the cover was a literal translation of the plot. For me, a much funnier idea is the H. L. Mencken cover Prejudices. But the solution was built into the material-l had a lousy photograph of Mencken. What could one do with a bad portrait of the guy? I cut up the photo into a silhouette of someone making a speech, which bore no relation to the shape of the photo. That was funny, in part because of the ironic cropping and because Mencken was such a curmudgeon. But not everything I do is intended to be funny, particularly when the subject matter doesn’t warrant it. Conversely, though I try to do things with a certain wit, I don’t always succeed.

SH: Can you be funny without a drawn line? Can type be an element of humor?

PR: Of course. One can make letters correspond to an action, like letting them lie down if a text is about resting or dying. Apollinaire did that kind of thing with his concrete poetry. And it was done long before Apollinaire. In Hebrew typography there’s a lot of humor. The way Hebrew was written in the Bible involves all sorts of grammatical tricks. And even when one prays, the prayers are written so that prefixes or suffixes are repeated. These were used as mnemonic devices. Indeed, humor is very Jewish.

SH: Jumping from ancient Israel back to logos, the NeXT logo is a very humorous approach.

PR: Humor was not intended. It’s playful and friendly. One critic described it as a child’s building block. While that wasn’t the idea, it does suggest the association. One can’t make people perceive ideas as intended. Actually, I assumed that Steve Jobs, the founder of NeXT and the man behind the Apple computer, liked cute things, like the Apple logo in rainbow colors with a bite taken out of it. I was told that the reason it was called Apple was that Jobs challenged his staff to come up with an idea-and nobody did-so he decided upon the apple, for no other reason than he liked them. This is a classic example of how arbitrary symbols and logos are-or even should be.

SH: Calling the computer an Apple also humanized it.

PR: Yes, I think by accident. But it’s evidence that a logo does not have to illustrate one’s business. If it does, great. Look at the symbol of a bat for Bacardi rum or the alligator for Lacoste sports clothes. Other than the originator, who really wants a bat or an alligator for a corporate symbol? But these are so ingrained in the consumer’s mind that it doesn’t really matter. The fact is, if one recognizes a bat or an alligator in association with these products, its purpose has been served. The function of a signature, which is what a logo really is, is to be authoritative and not necessarily original at humorous.

SH: Right, but we were discussing your reason for selecting the NeXT cube.

PR: I have a tendency to veer off. The reason was, Jobs liked cutesy things. I believed that I should try to find some kind of object, like a cube. It seemed reasonable because Jobs indicated that his computer was going to be housed in a cube. He did not say, however, that I should use a cube-he just shot off a bunch of adjectives describing the machine. I thought, what’s comparable to a cute little apple? A little cube-something to play with. And it was positioned askew on the envelope, like a Christmas seal.

Someone at the presentation meeting told me the thing that sold him on this logo was just that-the skewed logos-which is amusing because I originally did two versions. The first showed the logo parallel to the picture plane. The only one that was askew was the one on the back of the envelope. While the presentation was being printed, someone asked, “Why don’t you do them all like they appear on the envelope?” I agreed. That made it more playful and more lively.

SH: It’s like timing in the delivery of a joke.

PR: Yes.

SH: Have you ever done parody?

PR: I’ve done a poster for Yale that I would call parody in which I use the step motif-so common today among the trendy. But this old ziggurat motif goes back to ancient times. It is also a common motif in Dutch architecture. It’s a common motif that has been dragged out by the postmodernists. Because of all this charged meaning, I decided to do a parody of it, just for fun.

It’s a recruiting poster in the form of an accordion folder. The cover shows the title and a dramatized rendition of the step motif. When it’s opened, the Yale Bulldog is occupying the top step. I’m trying to take the cliche out of cliches. Cezanne’s apples were cliches.

SH: Wouldn’t you agree with the saying “Nothing is new under the sun”? Everything is a cliche.

PR: Almost everything is grist for the creative mill.

SH: Leon Trotsky once wrote that art is a complicated act of twisting and turning old forms that are influenced by stimuli outside of art so that they become new again.

PR: I’m not sure what Trotsky means by “old forms.” Does he mean old categories, old ideas—the way things used to be done, old content? The designer’s problem has always been to do something with content, old of new, to enhance, to intensify, to dramatize, with uncommon ideas or unusual points of view, and to treat these ideas in a practical way by formal manipulation—sensitive interpretation, with integrity and, if possible, with wit. Mies van der Rohe once said that being good is more important than being original. Originality is a product, not an intention.